- Title: Liminal

- Author: Douglas Reid Skinner

- Publisher: uHlanga Press

- Number of pages: 77

- Year of publication: 2017

- Category: Poetry

Liminal is Douglas Reid Skinner’s seventh collection of poems, and the age and experience of the poet are obvious throughout the collection. Although he is one of South Africa’s most prolific poets, he is not a canonised poet because of the politics and dynamics of canonisation.

South African literature has been fixated on apartheid for long, and the situation required contributions from both black and white authors. After apartheid came to an end, South African literature remained bogged down by the ghost of apartheid. Many authors were concerned about its ubiquitous presence and the shocking continuation of social vices despite the proclamations of racial equality. Skinner’s collection, published in a period of political upheavals in the country, discusses sundry issues, unlike many other collections that are preoccupied with only social issues. This shows maturity on the part of the poet.

Comprising thirty-nine poems and divided into four parts, the collection is a well-crafted one that features thoughtful and meditative poems. The poems deal with varied issues and are well-arranged to reflect their importance to the poet. Many of the poems are dedicated to people and the names of those people are etched right under the titles. Also, the locations where the poems were produced and the year of production are written on some of them. These para-textual features indicate the significance of the poems to the poet, and suggest that the poet has been on the move and that the collection was written over the course of some years.

Nature is a recurring motif throughout the collection. In ‘Surrounded by Mountains’, words like cloud, leaves, sunlight, forest and hills paint pictures of nature. The poem also reads like a discourse on eco-criticism, as it engages the issues of pollution, travelling, temperature and the economy. The motif of nature recurs in several other poems, including ‘Out of a Summer Night May Come’, ‘Leisurely Clouds’, ‘Smoke Signals’ and ‘Cloud Rise on Hills’.

The poet also employs storytelling in the collection. Each poem narrates a story, with vivid images created by the narration. ‘Winding Tunnels’ which is divided into four stanzas exemplifies this vivid use of imagery:

The road to Port Alfred unwraps and winds,

up over hills that rise to the south of town.

Long stretches are marred by bumps and cracks,

a patchwork of repairs now always in need

of the kind of attention it will never receive (p 18).

It is perhaps in ‘Prospects’ that the storytelling is most noticeable. The poem begins thus:

As the story goes, back in the Seventies

an old black prospector walked alone

in mountains up north, every so often

dropping by the Poffader Hotel (p 55).

Similarly, personification is used to empower inanimate objects and give them human features in order to strengthen the images created by the poet. There are many important features that make the collection a masterpiece; the impressive use of imagery is one of them.

‘In Perspective’ features names of people and allusions to things. The poem begins like a conversation where the poet-persona recounts an experience:

I must have asked Robert’s daughter to stand,

Just inside the frame with a shovel in her hand,

Because a photographer once taught me to make

Sure that the viewer has a sense of size and space (p 19).

The principles of writing and the many factors involved in the writing process are discussed in several poems and from several perspectives. The poem, ‘If You Think You Know How to Write a Poem, Think Again; the Poem Has Other Ideas’ chronicles the struggles of writing poetry. Written in thirteen couplets, the poem flows from despair to uncertainty and uses human beings as a metaphor for poetry and the process of writing.

In the same vein, the concept of inspiration is engaged in the poem, ‘Islands’. The poet writes:

“If I could only recollect exactly what I wrote

In the dream last night,” he thought. “It was

A solution of sorts, even an answer, perhaps” (p 48).

The anguish that often accompanies the creative process is also detailed in that poem. It ends on a dejected note:

“[N]ow that I’m ready with a pen and blank page.”

But there are no doors into our dreams.

Each mutely drifts along on its own sea (p 48).

In ‘Instructions for Writing a Poem’, the poet satirises the process of poetic composition through a poet-persona who desires to create a poem and is contemplating how to do so. The dream motif is used in the poem as a symbol for the muse that inspires the poet.

The health implications of adopting a single writing position are addressed in ‘Equilibrium’. The rigorous process of writing and the stress that comes with it are chronicled thus:

Writing all day can ruin a shoulder

if you’re not careful. All that leaning

on one limb as spring moves the blood

awful deep, making you rise early again

to take step after step across the void

on the old, uncertain, knotted string

you keep meaning to mend, despite

never having figured out how

you might do it – at least not yet (p 29).

‘The Poet’ discusses the age-long issue of the relationship between poetry and philosophy, quoting from Plato’s Republic. The poem discusses what the roles of a poet are in society. In just eight lines, it emphasises the struggles of many poets who contemplate whether to write for the society or to write as they feel. It says that a poet ‘offers no solutions…’, quoting Tony Hoagland, a prominent American poet. Ending on a pensive note, the poem states:

But what can you do

when you’re up to the neck

in a host of words

with only the shadow

of a spade to hand (p 51)?

Instead of writing socially committed poetry, which is what is often touted as African poetry, Skinner writes poetry that is uninhibited by society. The poems are personal and reflective. There is a suggestion that the act of composition should transcend cultures and societies.

However, the collection is not all art for art’s sake. Some of the poems suggest concerns for some of South Africa’s problems. ‘Prospects’ (p 55) reminds the reader of the story of South Africa’s mining fields. The corruption, the dangers involved and the controversies surrounding those fields are discussed. The metaphor of flags is used in ‘Flags’ (p 60) as a means of satirising resistance movements. The poet throws subtle jabs at the leaders of the victorious movement, throughout the poem they rejoice and reminisce on their victory without making a new plan. This could be read as a challenge to the anti-apartheid movements, for even after the battle against apartheid is won, the Rainbow Nation remains a haven of inequality and insecurity.

In the same vein, ‘Accounting’ (p 62) reflects on loss and oppression. In journalism, victims are often reduced to numbers, with their names left out of reports. The poem shows the hypocrisy of history’s gatekeepers, and it has a line that claims, ‘History is a slaughterhouse’. The title signifies the process of documenting and recording all victims of rapes, pogroms, terrorist attacks and other forms of indiscriminate killings.

Ezra Pound is alluded to in the collection. The collection also features a few instances of Grecian allusion, aside from the reference to Plato, and the allusions are explained in a section tagged ‘Notes’, at the end of the collection. The poems read like formal poetry as the poet recounts cognate experiences. Conversations are used in the poems and some involve dramatic monologue which sustain the narrative. The arrangement of the poems reminds one of the Elizabethan period, adjudged as one of the golden ages of English poetry.

Despite the simple language used, the poet uses vivid imagery to ensure that depth is sustained. The order of the arrangement of the poems and the division into stanzas and sections also aid the tidiness of the collection, and the concern for order trumps the concern for rhyme and rhythm. Some of the poems are long, extending to over twenty lines while some others are short. ‘Gravity’ (p 43) is just four lines and it is arranged in a manner reminiscent of George Herbert.

The collection is obviously the work of a master poet. Douglas Reid Skinner is a grossly underrated poet whose collection is meticulous and well-written. One can only hope that such an important poet gets more critical acclaim.

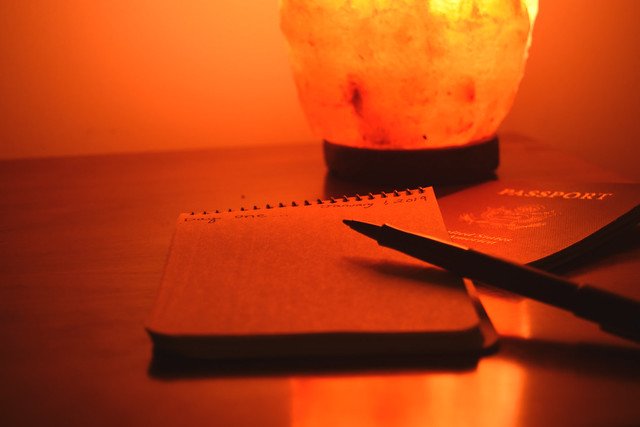

Photography: ‘Blank Page’ by Nick Amoscato

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.