By Vuyo Mzini

- Title: Makwala

- Author: E E Sule

- Publisher: Parrésia Publishers Ltd

- Number of pages: 326

- Year of publication: 2018

- Category: Fiction

In a 2013 interview on YouTube with Commonwealth Writers, as part of the publicity for his winning the Commonwealth Book Prize for the Africa region, E E Sule describes the inspiration for his 2012 debut novel, Sterile Sky, as the traumatic background in which he grew up in Kano City at a time of poverty and religious violence:

I keep remembering, in a very dramatic way, in fact it kept coming to me as a nightmare, that [my family and I] were hearing the sounds of death around us.

Sule injects this energy of violence and terror into Makwala, his sophomore novel, which was nominated in 2019 for the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) Prose Fiction Prize. In Makwala, Sule produces a captivating story about the complexities of survival in Nigeria’s poverty-stricken townships. The author creates a collage of perspectives from multiple characters. Four of these are primary to the resulting story. There are Jackson and Ende, two troubled youths living in the slum of Makwala, in Kano State, in northern Nigeria. There is Martha, Jackson’s mother, whose backstory is narrated extensively. The most prominent protagonist, however, is Odula, Ende’s father. In Sule’s intermittent switching from the third person to the first person narrative, Odula is the only character afforded the privilege of his own voice.

The main plot of the novel centres on the unearthing of each character’s formative life experiences. Teenager Ende lives with his father, Odula, in a small room in a compound with a few other families. Throughout the book, he pesters his father about the whereabouts of his mother. Odula is stingy with the information. He tells himself that he needs his son to be at a more mature age before he can reveal the peculiar circumstances of the boy’s birth. He knows, however, that it is his embarrassment that prevents him from telling of the dirty yet endearing encounter that led to Ende’s birth. When he finally decides to reveal the truth, he takes Ende on a treasure hunt by bus to an area called Naibawa. On arrival at a random spot, he hands his son a spade to dig for a mysterious bag hidden years ago. Odula is consistently coy about Ende’s mother, even at this intriguing moment of Ende’s digging:

Ende was anxious for an explanation. He looked from his father to the strange object removed from the earth. ‘Dad what’s going on?’ Odula stood up slowly. ‘Let’s go home’. In a raised voice, Ende, blinking rapidly, said, ‘Dad tell me what’s going on? What is in this bag?’

‘Calm down son.’

‘I’ll tear the bag! I want to see what’s inside’ (p 252).

Ende’s frustrations with his father’s reticence lead him to an unexplained mental illness and results in his disappearance at the end of the book, in search of his mother.

Martha’s life journey is about the disillusionment of young women in their struggles for happy and successful lives in the city. She characterises the typical story of a search for prosperity gone wrong. She was brought to Kano City as an innocent village girl by a woman from her village named Madame V, under the pretext of employment. On arriving in the city and discovering that the job opportunity is that of a sex worker, she declines, much to the disbelief of Madame V:

The woman, a buxom radiant veteran, cackled, clapping her hands…‘Angel Martha! Na angel you be na. Wetin you wan do? Work for office, abi sell for market?’

‘I wan sell for market,’ Martha had said.

‘E better make you use your nyash make money first before you go buy tings sell for market. You hear? (p 43).

Madame V then orchestrates the rape of Martha in an attempt to coerce her into the sex work industry. Martha’s resistance comes to nought as her ambitions for further studies and transcending the industry are thwarted. She continues to use her body as a source of income. When we meet Martha in the novel, she is in a relatively comfortable space with her work, but her backstory is a harrowing narrative of experiences that led her to entering the oldest profession. Sule contrasts Martha’s agency as an empowered woman engaging in sex work as a means of living her best life with the power dynamics of big men and their assumed entitlement to women’s bodies, as she endures humiliating abuse at work.

Equally disturbing is the exposure that Martha’s son, Jackson, has to this world of sex work and rape. Jackson is a product of an unrequited love that Martha had for a Lebanese mercenary. With the nickname ‘Lebanese Pikin’, Jackson’s light skin attracts all sorts of unwanted attention, including schoolyard bullying and paedophilic gazes from older men and women. His experiences of both observing and experiencing rape render him a psychopath of sorts, one who makes disturbing drawings of deaths involving mostly his mother. This disturbing craft is the result of a combination of growing up in poverty, the troubles of colourism and being left by his working mother with questionable characters, some of who allow him to watch pornographic films despite his young age. The drawings come to life as by the end of the book Jackson has murdered two people and is on the run from the police. Sule introduces an interesting idea with Jackson’s formative discovery in the story. In his hour of need, Jackson is sexually exploited by men, an echo of the experience his own mother endures in order to survive. This shared experience does not, however, bring a pleasant resolution to the tensions in this mother-son relationship.

Odula is revealed in the book as one who lacks the courage expected of him by those who depend on him. On one account, he abandons an entire family when the Nigerian economy of the early 1990s causes him to lose his job as a policeman and his wife’s business to fall apart. On another account, his fear and embarrassment lead to the death of a woman in childbirth, a thing that could have been avoided with a simple visit to a hospital. Odula even lacks the courage to tell his new love, Martha, that he would like her to stop the sex work and save her body from the torture:

She had told him, ‘Many men, only God knows where they come from, enter this room with big rods between their legs and chuck them inside me anyhow. After all, they pay money for it. You hear?’ He wanted to tell her that she could do other things instead of taking their money and the pain. But he had no courage (p 140).

Sule’s novel has a bustling energy, reminiscent of life in a slum. The book attempts to explore all types of complexities across a number of categories including classism, colourism, sexuality, feminism and religion. In trying to tackle all these things, there is some confusion as to the agenda or message of the author. As an example, there is a clear agency that women have in the book, with all the female characters engaging in self-determining entrepreneurship, from Mama Maria and her Sharia-defying alcohol selling to Hajiya Kende, the restaurant owner who helps Odula take care of his new born baby, cleaning and feeding a motherless baby Ende, to Odula’s first wife, Ijaguwa, who we are told was, ‘An incurable believer in hard work…she put all her energy into business’ (p 255). But there are subtle and perhaps inadvertent admonishments that suggest that the author judges women’s choices harshly. Mama Maria is questioned on whether she is a good mother, having four daughters by four different men. Jackson’s mental state is also attributed to his mother’s occupation. There is also a passing moment when Odula’s delinquency towards his family is attributed not to his father but to his deceased mother:

Seeming to be more interested in attacking, [Odula’s uncle] said, ‘You’re the heir and you failed to come bury your father. You must have taken after your stupid mother who didn’t get a burial from you either’ (p 277).

The lack of detail on Odula’s parents, except for this little snippet, suggests that the derisive comment about his mother is an intentional insertion by Sule. There is an undertow of misogyny as well as confusion that arises from the many elements that Sule tries to juggle in the book. It is similar to how, not knowing his background fully, one might think Fela Anikulapo-Kuti was a feminist when he said, ‘Lady na master’, in his 1972 single, ‘Lady’.

The novel Makwala is a story of discovering the many layers that affect people living in poverty. It is a sojourn in the slums of Nigeria and an engagement with the moral complexities of balancing survival and happiness. The experiences depicted are traumatic but provide a realistic platform for the debates on modern-day interlocking systems of power, the major ones being class, race, gender and sexuality. It is a lot, and as Kuti would say, ‘I never tell you finish’.

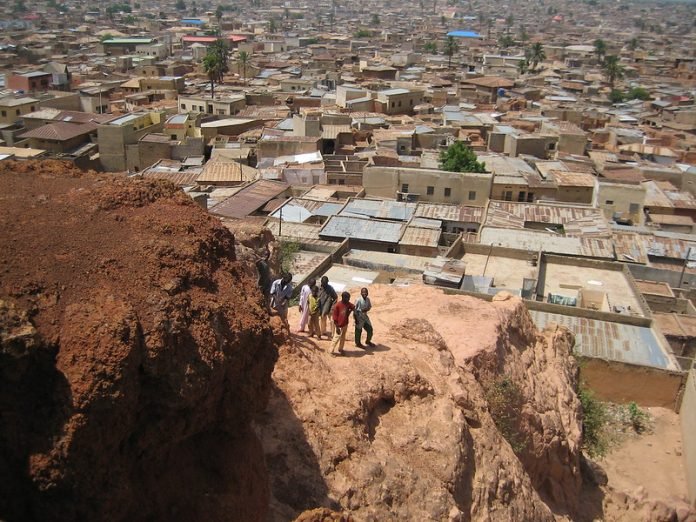

Photograph: ‘Kids Playing on Dalla Hill’ by Eugene Kim

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.