- Title: Life, Love, Lies

- Author: Fonkeng E f

- Publisher: Langaa RPCIG

- Number of pages: 32

- Year of publication: 2015

- Category: Essays

Life, Love, Lies reads like a Twitter rant. What is contained in the book is the conclusion of a thought process, but we are not privy to the thought process itself. This makes the conclusion both difficult and easy to disagree with. At the end of it, the meaning-making of the book is subjective, just as our meaning-making, everyone of us, is subjective.

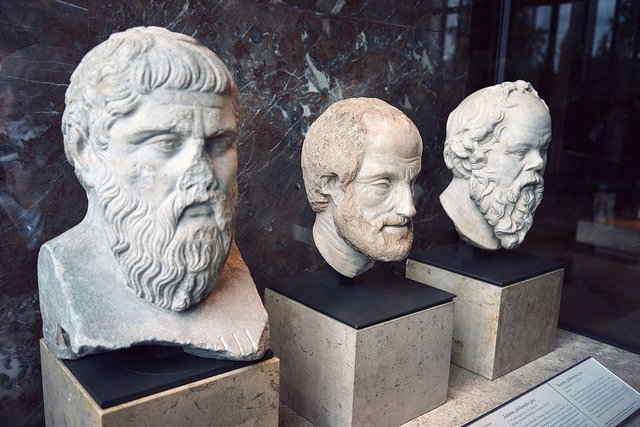

Life, Love, Lies is a book full of contradictions. The introductory note first warns that these ‘reflections are not presented as philosophy, nay theology’ and then it cautions the reader to ‘stay off the more or less mysterious path even if a number of reflections might end up projecting that (Socratic-Aristotelian-Platonic) aura’.

The book’s claim raises the question: what is philosophy if it is not that attitude that acts as a guide to behaviour? What is the function of philosophy if it does not cause us to reflect, think and question what we know? What else is the function of philosophy?

The modern notion that philosophy is just an academic discipline is a very narrow-minded one. Philosophy, too, is advice given by parents to their children. Philosophy, too, is what one learns when one reads stories. It is what helps us in making decisions and choices. It is us.

The book, in the end, does everything that it says not to do. It is a paradox. But is that not what life is? Sometimes, we seem to understand life and then we lose our grasp of it.

Life, Love, Lies is a collection of short-length reflections that concerns itself with love and life, and the ‘lies’ in-between. ‘Lies’, in the context of the book, is not necessarily untruth but rather challenging the status quo. ‘Lies’ is pausing and asking questions rather than taking as truth that which has been recycled. Within the framework of the book, truth, in itself, is an opinion.

The first page of Life, Love, Lies begins with a startling line, ‘Art is Man is art’. Perhaps if art is understood, the nature of man will be comprehendible. In the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, we read:

The definition of art is controversial in contemporary philosophy. Whether art can be defined has also been a matter of controversy. The philosophical usefulness of a definition of art has also been debated.

No wonder the author of Life, Love, Lies ends up advancing his idea on Art and Man no further than, ‘[The] only logical counsel is to rise, dust off, grab on to yet another saying and move on’.

Do we just move on from one saying to another because we do not understand Man? Do we get to escape the burden of the human condition? Do we disengage the human essence and its agency? These existential questions are critical to the restoration of faith in life, at least.

There is no right or wrong, only time.

Right and wrong belong to the past but are shaped by the future (p 1).

We encounter ‘right or wrong’ on the fourth line of the first page of Life, Love, Lies but we have not encountered anything before it that touches on the subject of right and wrong. The sentence preceding the two that are quoted above reads, ‘Every success hides many a failure’. Perhaps we are to read every line of the first page as a standalone thought.

That fourth line has echoes of the ‘Philosophers vs Sophists’ debate. The Philosophers believe we can mine truth through empiricism or reasoning whilst the Sophists believe truth is a human construction and that there is nothing like ultimate truth.

If the author advances the position that there is no right or wrong, could it be that he thinks there is no such thing as a right or a wrong? Could it be that he means that truth, as right or wrong, is not absolute and that there are grey areas, relativism? What happens to morality, ethics and religion then? Can morality be devoid of God?

Unfortunately, we do not find evidence of what the author’s thoughts are in the text. The evidence that we have in the book is that the author subtly engages the questions that occupied Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. However, the author’s submissions are questions that leave no clues to answers.

Perhaps what is relevant in the two sentences quoted above is the idea that truth is tied to time. In the sociological sense, there are three times: the past, the present and the future. What remains largely unknown among those three is the future. Why then, one might wonder, does it shape the past that is already known?

Explaining the paradox of time in The Boundaries of Human Knowledge Stephen Lehar argues that:

In physics there is no such distinction, any instant of time can be set arbitrarily as the origin t = 0, but in fact that particular moment in time is no different in principle than any other moment in past or future. In physics, time is a dimension, much like space, and in modern physics space and time are combined in the notion of spacetime. Let us suppose, hypothetically speaking, that physics is right, and that there is no flow of time, every moment is like every other. We can imagine a series of events as a length of a movie strip, whose individual frames can be viewed in succession through a movie projector, but that the succession is actually illusory, and that real time underlying the illusion is the movie strip itself, as if laid out on a table, with past towards the left and future towards the right. This results in a deterministic view of reality in which the final outcome is predetermined, and there is no longer anything like “free will” as we normally conceive it. And yet the characters recorded in the movie strip behave exactly as if they do have free will. At one point one character decides to take this action instead of that, and every time we go back to that point in the movie we see that same character exercising his free will again by making the same choice. The free choice is frozen in time when viewed externally, outside of time, but to the character there is nevertheless a free choice that he experiences as occurring at that point in time, as when viewing the film strip in sequence through a projector. Every frame in the movie sequence is perceived as the present moment, framed between leftward past and rightward future events, and yet as in physics, this perception is illusory, because in fact every instant is equal to every other, the past and future directions being merely relative.

Lehar provides an explanation of the paradox of time that Life, Love, Lies merely gestures towards. Again, what appears in Life, Love, Lies leaves us with the feeling that we have been starved of something important. For example, we do not know the views of the author on ‘free will’.

The book also takes on everyday sayings and questions the wisdom (or logic) of a lot of things that have been committed to the collective memory. The author writes, ‘Living room. So, all the other rooms in the house are not worth living or what?’ (p 2). Elsewhere we read, ‘A bird in hand is worth two in the bush. But you still have to go to the bush to catch that one’ (p 8).

There is also political commentary. ‘I never ran into a politrician who lost, only those who lieing luck ran out’ (p 6). We infer from this that politicians are tricksters who lie. Language is intentionally distorted so as to stress a point. Lying is spelt as ‘lieing’ and politician as ‘politrician’.

‘Jesse ran so that Barack could win’ (p 11). This is an allusion to US politics in relation to blacks as president. Rev Jesse Jackson was a candidate for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow US Senator for the District of Columbia from 1991 to 1997. Richard Hatcher, reflecting on Rev Jackson’s attempt to secure the Democratic Party’s nomination, says:

By those two campaigns, he changed the political landscape of the country. And really, I think, created in the minds of the general public a level of acceptance of a Black candidate for President that had never existed before. It never existed before. The very picture, I remember Percy Sutton from New York talking about an old Black woman up in Harlem when somebody had said, ‘Well you know Jesse Jackson can’t win this election. You know, he doesn’t have a chance’. And this woman saying – ‘But we be winning all the time. Whenever I see him on television, up there arguing with those white men, tell them, give them as much as he takes, we be winning’.

And in 2008, when Obama was announced the new president of the United States, Rev Jackson watched on, crying. How long he had walked in such a short distance.

The author of Life, Love, Lies muses on the idea of love, too. ‘Marriage is to love as water is to oil’ (p 23). Water and oil do not mix. They form a suspension instead of a solution. ‘Marriage or love? Stop being selfish, my friends, and choose’ (p 23). The reader might wonder, should love and marriage be independent of each other? ‘Marriage, love’s prisoner’ (p 23).

Life, Love, Lies may be a difficult read. It is a book for the free spirit. Whilst it questions many things, it is limited by the ‘misfortune of language’ as Emmanuel Iduma, quoting Roland Barthes, puts it in ‘Trans-wander’. To call something by its name is to tacitly admit both its absence and presence. That is what this book suffers from. However, that in itself is not a failure.

Photograph: ‘Plato, Aristotle, & Socrates’ by MARCO_POLO!

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.