- Title: The Televangelist

- Author: Ibrahim Essa

- Translator: Jonathan Wright

- Publisher: Hoopoe

- Number of pages: 483

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Fiction

In keeping with the need, in this age, for thorough intellectual scrutiny of dearly held beliefs, Ibrahim Essa deploys his novel, The Televangelist, as a means of examining and contesting the hegemony of Islamic ideology in twenty-first-century Egypt. Crammed into the 483-paged novel is a fusion of Islamic theology and socio-political analysis with a double dose of wit, as expected of the satire that it is. Engaging the reader on these levels, Essa lays out his own thesis on religion and the State’s involvement in it.

Sheikh Hatem el-Shenawi is the televangelist. He has studied Islamic jurisprudence and is versed in Islamic theology – almost too learned to be at peace with himself. Having concluded his studies and qualified as a preacher, Hatem begins preaching in a small mosque from where his fame as a preacher and Quran reciter spreads rapidly, bringing him to the television screen and lifting him to the heights of public esteem. The charismatic preacher that he is, Hatem knows what exactly to preach on television: just the kind of fluffy, surface stuff that satisfies his audience’s and sponsor’s itching ears, and not the vigorously researched conclusions he has reached about his religion. As he is struggling to balance these two aspects of himself – the charismatic television preacher and the rational, erudite cleric – he is also battling for his wife’s love, attention and respect and his son’s mental health.

It is not unexpected that one of the brightest preachers in Egypt is monitored not only by the State but also by the president’s son. When the president’s son-in-law, Hassan, falls into the abominable sin of converting to Christianity, the unenviable duty of bringing him back to his senses falls to Hatem. While he is at it, Nashwa, a beautiful actress comes into the picture. She is employed by the State to get hold of a document that Sheikh Mukhtar leaves, on his way out of Egypt to Saudi Arabia, in the care of his friend, Hatem. Sheikh Mukhtar is also an Islamic preacher, and he is being persecuted by the State for his inability to find a solution to the president’s son’s incessant ‘nightmares’ and for wanting to know more than is good for him. Already bereft of attention and love from his wife, Hatem falls in love with Nashwa who is equally enamoured with him. While entangled in this mesh, he becomes disillusioned with the government and lets Hassan loose, charging him to find God through careful study.

Hatem’s failure to discourage Hassan from converting to Christianity and his friendship with Sheikh Mukhtar spell the end of his television career. The Ministry of the Interior blacklists him and suspends his television programmes. He goes on a retreat with his wife, whose sympathy and friendship he has begun to win, but the retreat ends abruptly when he discovers that his wife cheated on him. This revelation is soon overshadowed by the bombing of a Coptic church. The State calls on Hatem to join other sheikhs in paying the Pope a condolence visit, a visit that reveals in the end that they all – Hatem, the president’s son, the State, and even the Pope – have been victims of a grand deception and one young man has proved smarter than them all.

Essa’s The Televangelist is a bold reflection on the Egyptian State. First, he chooses to construct his story around a religious figure in whom we find the delicate mixture of the old and the new. To Essa’s credit, Hatem is a well-developed character: he is quick-witted, humorous, practical, sarcastic, serious, simple, scholarly, saintly and sinful. Hatem belongs to the generation of Islamic preachers that straddle tradition and modernity, a position that gives him the advantage of striking the ideological balance on hotly contested theological theses. But to be sure, Essa does not merely set the protagonist up to offer alternative explanations to the many hadiths that have always embarrassed Muslims (take, for example, Mohammed’s marriage to the wife of his adopted son or his prescription that if a woman wants to avoid committing adultery with a man she should breastfeed the man ten times, later five, so that the man would become like an adopted son to her) rather, through Hatem, he challenges Muslims to confront these embarrassments and subject their faith to the scrutiny of reason.

Furthermore, through Hatem, Essa holds up for public analysis the character of preachers. He pursues the objective of establishing the humanity of religious preachers. We read this at the very beginning of the novel:

Hatem spoke with such solemnity, recited the Quran so eloquently, and was so quick with sayings of the Prophet and stories from the Prophet’s life that it came across as a contradiction when he spoke in a way that didn’t conform to the usual image. It took people by surprise but, at least, as far as Sheikh Hatem could see, they approved of the fact that a preacher who gave fatwas was a man like them, a man who sometimes spoke rudely, who had material demands, and who liked to say outlandish things (p 2).

Essa employs many characters in projecting this motif, which runs through the novel. There are the sheikhs who grace many State banquets and gorge themselves on bowls of rice and lamb, and there is Sheikh Mukhtar, who can proudly trace his lineage to Prophet Muhammad but who insists he possesses no supernatural powers. This ties in with Essa’s authorial objective of calling his audience to subject their religious beliefs and preachers to critical examination.

The elephant in the room, which Essa really dares to address, is the fusion of religion and the State. Hatem, like other eminent sheikhs, is controlled remotely by the State: the State determines the content of his message to the public and the extent to which he is free to express his opinion on sensitive religious matters. The State also determines what to do with a hothead who suddenly abandons his religious beliefs and embraces another faith. According to Essa, through Hatem, a society where religion primarily sets the rule is ‘a broken society’ (p 155). This bold task that Essa takes upon himself is interesting in that history clearly paints Islam as a religion as well as a political ideology, what with the Sharia-governed Caliphate regimes that rose in the wake of the Islamic expansion, beginning in the seventh century, but Essa seems to reject this political dimension of Islam.

Also, commenting on Hassan’s apostasy, Hatem asks that the young man be left to choose any religion he pleases, provided he arrives at his choice through personal, thorough investigation. By this, Hatem (and, by extension, Essa) pits himself against one of the most respected sources of the deeds and sayings of Prophet Muhammad:

[By] Allah, Allah’s Apostle never killed anyone except in one of the following three situations: (1) A person who killed somebody unjustly, was killed (in Qisas,) (2) a married person who committed illegal sexual intercourse and (3) a man who fought against Allah and His Apostle and deserted Islam and became an apostate (Sahih Bukhari, Volume 9, Book 83, Number 37).

Essa’s position is a call for the reformation of Islam. If, indeed, as Essa argues, Muslims subject these sources and even the Quran to rational examination, the world will see less of the violence perpetrated in the name of Allah.

Despite occasional grammatical infelicities and one or two poorly developed characters (the actor Nader Nour, for instance), The Televangelist is an effective critique of the shortcomings of the Egyptian State. Its strength lies in its humour, honesty and depth. It is definitely worth the time devoted to its reading.

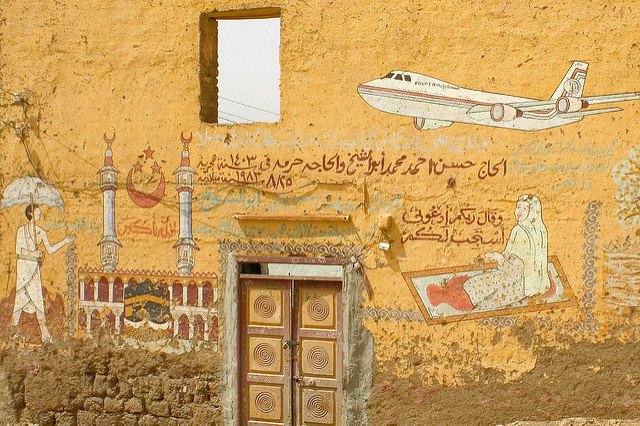

Photograph: ‘To Mecca and Back’ by Christopher Rose

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.