- Title: Who Told the Most Incredible Story?

- Author: Naana J E S Opoku-Agyemang

- Publisher: Afram Publishers (Ghana) Limited

- Number of pages: 619 (5 Vols: Vol 1, 113pp; Vol 2, 121pp; Vol 3, 128pp; Vol 4, 122pp; Vol 5, 135pp)

- Year of publication: 2015

- Category: Children

‘“Fantasy” is the natural bedrock of all African folktales. In other words, there is no African oral narrative, including folktales, both “fictional” and “non-fictional”, that is not couched in varying degrees of fantasy’, writes Ademola Dasylva in his monograph, Classificatory Paradigms in African Oral Narrative (p 14). It is often said that childlike truths are best expressed in a childlike manner, and fantasy is a sure means of perpetuating childlike truths. Fantasy allows free range for the imagination of oral artists and their listeners.

It should be noted at this juncture that fantasy is not only limited to the world of children in the African oral tradition. The beliefs that validate African cosmology and worldview are also couched in fantasy. The Ifá corpus is a case in point. Yorùbá incantations, shot through with fantasy, are another case in point. In the world of African fantasy, not everything is exaggerated and embellished for mere make-believe; the stories are not just fables for fun. They are sometimes told and preserved to trace a family pedigree, to codify and maintain judicial laws, to valorise warriors and ancestors, and to validate religious belief. They can sometimes be used as a way of socialising and integrating both children and adults into society, instructing them in the social values they are expected to uphold. Therefore, the African oral tradition is a subtle way of moralising a people.

In a paper titled ‘Gender-Role Perceptions in the Akan Folktale’, Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang advances the functionality of African oral literature further:

Usually in the [primary oral culture] the folktale constitutes a major, early source for the liberation of the imagination. Built largely on fantasy, the tale has therapeutic, emotional, and cathartic usefulness as well as didactic functions. This literary art form provides a passageway through which society confirms its strengths and growth strategies, while inducting new generations into its life-flow.

And this position is further dissertated on in a volume titled Power, Marginality and African Oral Literature, edited by Graham Furniss and Liz Gunner:

African oral literature, like other forms of popular culture, is not merely folksy, domestic entertainment but a domain in which individuals in a variety of social roles are free to comment on power relations in society. It can also be a significant agent of change capable of directing, provoking, preventing, overturning and recasting perceptions of social reality.

Though fantasy and the functionality of African oral literature have been ever present in African literature, they are gaining more momentum in contemporary writing such that in recent books, especially by West African writers, one needs not labour much to recognise the presence of these features. The Nigerian writer, Okey Ndibe, in his recent memoir, Never Look an American in the Eye, dedicates a chapter to the memory of his childhood titled ‘An African Folktale: A Wallstreet Lesson’, in respect, again, to our twin corollaries:

[The] storytelling sessions were a marvelous postprandial treat. The folktales featured both human and animal characters, but mostly the latter. They were also of different kinds. Some were meant to foster moral acumen in children; these often dramatized the consequences of making ill-advised choices. Some were calculated to answer quasi-biological or mythic questions: Why don’t women grow beards? or Why does the tortoise have a broken shell? or Why did God leave the world to make a home in the sky? or How did the lion become king of all animals? or Why do people eat the chicken most of all the animals? Some of the folk tales were for old-fashioned fun, sheer delectation (p 165).

The book under review, Who Told the Most Incredible Story? by Opoku-Agyemang, is a five-volume collection of folk tales. Opoku-Agyemang is a respected academic. She is Ghana’s immediate former Minister for Education and the first woman to serve as Vice Chancellor of a Ghanaian university. She has written extensively on African oral literature.

The collection is a beautiful compilation of West African folk tales, with a Ghanaian label. The tales are didactic and cathartic but the reader is also treated to exhilarating entertainment. The five-volume collection includes: How Dog’s Nose Became Dark and Other Stories (Vol 1), The Corpse that Laughed and Other Stories (Vol 2), The Singing Competition and Other Stories (Vol 3), The Spread of Wisdom and Other Stories (Vol 4), and Why Tigers and Leopards Do Not Mix and Other Stories (Vol 5).

One of the stories in the first volume is titled ‘How Dog’s Nose Became Dark’ (p 1). It is one of those fables that try to explain the biological and physical makeup of things, people or animals, and at the same time teach morals from the flaws of its subject. The fable explains the reason for the moistness of the dog’s nose using African fantasy. While there is also a Christian legend about the wetness of the dog’s nose and scientific proof, this story offers an African dimension to this characteristic of the dog.

The fable centres on three good friends: Dog, Hen and Goat. One day, Dog airs his frustration about their namelessness and suggests that they should adopt for themselves fitting names. This shows the concept and importance of naming in the African culture. His friends reason with him and they secretly adopt new names. But they cannot keep calm about it and humans soon find out. But from whom? The three converge again at their secret place and make a fire that they will pass over, and whoever it was that sold them out to humans would be burned by the fire.

The next story in the first volume is titled ‘Crocodile and the Birds’ (p 17). But first, can the reader imagine smooth skin on the crocodile, to the extent that it is the source of that animal’s pride? Just like the first fable in the volume, this story tries to explain certain truths about the nature of some animals. The story also condemns greediness and slyness. During a communal task, the birds show extraordinary commitment and outwork their fellow animals, and their fellows deem it fit to honour their diligence. But instead of having the feast at the lion’s palace, the natural habitat of birds is chosen for the feast. The birds are excited and while deliberating they propose that their friend, Crocodile, be their spokesman on the day of the feast. They gather their plumage for him and gum them to his back so he can fly with them. But before they leave, he tricks them into taking new names so that when food is served at the feast it would be clear which individual the food is meant for. He takes the name ‘All of You’. As a result of the stratagem, Crocodile claims for himself all the food brought to the birds. This infuriates the birds and they pluck off the feathers they gave him. Yet, he pleads with the birds to instruct his wife, upon their return to land, that she should provide a bed of feathers, clothes and soft materials for his safe landing. The birds twist the message to his wife, telling her that her husband requested a pad made from all sorts of stones, gravel and other hard materials to be made outside of his house. The rest of the story can be pieced together.

There is a Yorùbá variant of this story which has the tortoise as the trickster. This shows the regionality of the folk tales; they are collectively owned. These tales are sometimes adapted to suit the oral traditions of the community in which they are told. Variations may also occur in some of the folk tales as a result of the medium of transfer. At some point in their history, they were strictly orally preserved and as time passed, some of the details changed due to the memory or imagination of the oral artist, but however the characters may change, the message remains intact. In the context above, the crocodile is just as wily as the tortoise, and the logic of the narrative is not flawed by substituting one villain for the other.

In the second volume, The Corpse that Laughed and Other Stories, ‘Who Told the Most Incredible Story?’ (p 1) is really an incredible story. This type of folklore encourages creativity and heightens the imaginativeness of the listeners. It is also meant to entertain and ease pressure:

Onyame the Sky God offered a prize to the animal who would tell the most incredible story. The judges would be the audience, and the winner could choose anything he fancied, even the position of Onyame himself.

Most of the animals imagine themselves the winner, daydreaming about what they would ask as a reward for winning the contest instead of coming up with a story to tell. Pig, who is ‘lazy with insatiable appetite’, simply decides he is going to ask for an already farmed large plot of land and treat himself to all kinds of food. Mouse dreams of possessing authority enough to call the bluff of Lion and other animals: Elephant will be made to clear his farms and Snake to plant. Mouse’s wishful thinking is motivated by vengefulness against the large animals that command authority and other animals to whom he has always been prey. But when it is his turn to tell a story, he only stammers and the other animals laugh him out of the contest.

Then it is the turn of Moth and Mosquito to tell their incredible stories. Moth says before he was born his father became bedridden and he had to clear his father’s farm and do his other work. And due to Moth’s effort his father became a wealthy man before Moth was born. Mosquito says when he was four years old he killed an elephant all by himself. A whale tried to swallow him but he turned the whale inside out and released a shark. The absurd, the hyperboles, are further registered by the illustrations in the volume.

Fly’s story is that he shot an antelope with his gun, then ran forward, quartered the antelope and caught the bullet before it fell to the ground then put the bullet back in his gun. He claims to have climbed a tree, made a fire, cooked and eaten the entire antelope all alone. But being heavy after the buffet he could not get down, so he went to the village, got a rope and let himself down. Funny, isn’t it? And who would be the winner, given all the stories above? How to judge the incredibleness of these stories is an argument that is still raging on at Onyame’s palace till today.

Another thing about African folk tales is the diversity in characterisation. In volume three, The Singing Competition and Other Stories, there are folk tales with more human characters. ‘Between Wealth and Kindness’ and ‘How the Crow Acquired His Black and White Feathers’ are examples of tales which have human characters. ‘Between Wealth and Kindness’ (p 75) espouses the value of good neighbourliness and humbleness. In Biakaye village, a society where people do not lock their doors and everyone shares with everyone else, there are two wealthy men, Dogo and Bonto, who keep to themselves. They discriminate along the lines of class and social status and would rather not have anything to do with persons they consider of lower status. When it is right for them to get married and they seek maidens from the village they live in, they are snubbed by the so-called poor families. Nobody is willing to give his daughter in marriage to them, so they seek their brides outside their village. They get married in a beautiful event, which the villagers boycott. Upon return they move away from the people and build their houses on the outskirts of the village. Then comes the funeral of Dogo’s mother-in-law and no one goes to the ceremony. He invites his rich neighbours but they are too busy to honour his invitation. He is forced to call upon the village people. And how that funeral is turned into a feast, to the consternation of the two rich men, is something that wealth cannot buy.

‘The Tortoise and the Squirrel’ can be found in The Spread of Wisdom and Other Stories (p 39), the fourth volume of the collection. It is a story involving the notorious folklore trickster, Tortoise, one that highlights the importance of resisting the influence of bad friends. Tortoise and Squirrel are intimates who went through the same initiation rites, where the values of honesty and responsibility were to be instilled in them. The initiation ceremony is a way of inducting young adults into the fold of grownups, and it is not entirely surprising that this motif is exploited in this folk tale.

Tortoise, being the lazy animal that he is, does not imbibe the communal values. The dry season lingers, so nobody farms as everybody waits for the rains. However, Tortoise and Squirrel are happy about the situation. It means freedom from work for them. Finally, the rain comes in torrents and with thunder such that it wreaks havoc and dislodges huts. The neighbouring village is completely devastated, and the elders of Tortoise’s and Squirrel’s village decide that they must help their neighbours out. Tortoise and Squirrel will have none of it. Why should they assist the unfortunate when they are not the cause of their misfortune? Tortoise, being the cunning type, convinces Squirrel that they should run into the forest while the rest of their age group rallies around their neighbours. But while in the forest, Tortoise resorts to his stock-in-trade and Squirrel soon regrets his indolence.

The fifth and final volume of the collection, Why Tigers and Leopards Do Not Mix and Other Stories, offers more riveting folk tales, like ‘How Do Some People Show Their Gratitude?’ (p 105). This folk tale is subtle and poses a question about humans. How do humans really show gratitude and could they be bound by love or would it be wise to treat humans with distrust? These questions are the centrepiece of this folk tale.

There are three hunter friends who hunt together. One day, as they are trying to trap a grasscutter, it escapes into a hole. One of them pokes his hand into the hole and is stung by a cobra. But rather than disclose the danger and warn off his friends, he tricks them to suffer the same fate. The second hunter is also stung by the snake when he dips his hand into the hole and then realises that his friend does not want to suffer it all alone. Likewise, he also makes the last one suffer the same fate. When each one understands the danger he is in, he makes for the village but it is only the last of the three hunters that makes it home, and immediately he tells the villagers what has happened. He also dies. A search party of the Asafo group is then sent to the farm to kill the menacing cobra. Cobra hears the war songs of the search party from afar and scurries away. This is how he meets Hunter on the way, whom he begs to hide him around his waist while the Asafo group passes.

The search party meets Hunter on the way and relates what the evil Cobra has done to him. They ask whether he has seen Cobra but he denies and directs the group another way. As soon as they leave, Hunter tells Cobra he is safe to leave, but Cobra insists that he must also bite Hunter, to repay the favour. Bewildered, he asks why Cobra must do such an evil thing after he has saved Cobra from death. Cobra replies that that is the way of humans, how they usually repay gratitude. Cobra then proposes that they appoint a jury of three to adjudicate their existential case. Hunter picks Hen, Goat and Lion.

First, they meet Hen but she does not have anything favourable to say about humans. She says she is being maltreated by them. She lays eggs and hatches chickens, but it is humans that decide how many of her eggs should be used for rituals, how many for food, how many she can really hatch, when to sell or kill them for food. And to crown it all, she is not given grain to eat but booted away to go and search for food. Goat, too, does not have pleasant things to say about humans, and her story is even worse than Hen’s, which makes Cobra happy and puffy with joy. But the last juror is Lion. Hunter narrates the story to him too. He is so furious at the ingratitude of Cobra that he kills him at once for being so evil. He bids Hunter goodbye and warns him to be on the lookout for bad characters like Cobra. Hunter thanks him and goes home, but on his way he meets his relatives who tell him his wife is in labour and according to the medicine woman, they must find a lion’s bile to prepare the medicine that would save his wife.

A notable feature of these volumes are the stories involving the Akan folklore trickster, Kweku Ananse, also known as the spider. He makes appearances in all the volumes, appearing sometimes as a hero – outwitting other animals in difficult situations, proffering his wisdom to aid his neighbours – but mostly as a malevolent villain who comes undone by his own tricks. In this vein, a scholar of African oral literature, Alphonse Kwawisi Tekpetey, in his paper, ‘Kweku Ananse: A Psychoanalytical Approach’, examines this character using Freudian theory:

Ananse is revealed as an incarnation of the id with little or frequently no intervention of the superego. He is lawless, asocial, and amoral. One systematically finds him engaged in activities directed at gratifying his instincts for pleasure without regard for social conventions, legal ethics, or moral restraints. Kweku Ananse’s literary function in the Akan oral educational system appears to be an attempt to expose the danger that he represents in society. Besides, the audience sympathizes vicariously with our hero, who renders, within the fixed bounds of what is permitted, an experience of what is inadmissible. Ananse narratives are cathartic, serving as tension-relieving aesthetic devices.

In ‘Kweku Ananse and his Farm’ (p 45), this trickster displays his exceptional self-centredness, skillfullness in lying and cunning. He has a wife and three children. During a harvest, his farm is a wonder to behold as everything yielded bountifully. But he does not want anyone to share in the harvest and eat the fruit of their labour – he despises his wife and children. He therefore feigns dying, and on his deathbed he makes a request that he should be buried in his farm with cooking utensils and that nobody should visit the farm for a certain period. But one of his sons – Ananse always has a nemesis – is suspicious of his father and sneaks into the farm only to discover traces of cooked food, so he makes an effigy and places it in the farm to trap the trespasser. Everybody is bewildered the next day at the culprit found stuck to the effigy.

Who Told the Most Incredible Story? by Opoku-Agyemang is a treasure trove of the African folkloric tradition and a must-read for all, not only scholars interested in African oral literature. The folk tales contained in the collection are artfully illustrated to aid the imagination of readers, just like Yoruba Folktales by Amos Tutuola. Many themes run through the collection which are well suited to answer some contemporary questions and the wisdom gleaned from it is also applicable to the nuances of life’s everyday riddles.

The collection is written in simple language that is accessible to all age groups. These tales were in oral form and handed down the generations in different West African languages. However, Opoku-Agyemang as scrivener, her dexterity in translation should be praised for two things. The first is that almost nothing is lost in the English translation. The liveliness and ambience of the oral performance is well preserved; it is as if one is listening to an oral artist tell the stories. The text draws the reader in as though it were written in their mother tongue. The second is the style. African folksongs and parable are carefully used as the embellishments.

The oral storytelling tradition is not as vibrant as it once was. This collection offers the possibility of preserving and transferring these stories for many more generations. African oral literature is being taught in some African universities and outside the continent. Its teaching in the primary and secondary schools across Africa should also be encouraged. That is where the minds of teenagers can be best be moulded and shielded against the amoral and aggressive norms of the contemporary period. In fact, at the introduction of Western education in Akanland, it was said that storytelling was included in the curriculum of the Akan and Guan primary schools of Ghana. Finally, because of the functionality of African oral literature, there is a need to repurpose it for usability across multiple media and for multiple audiences.

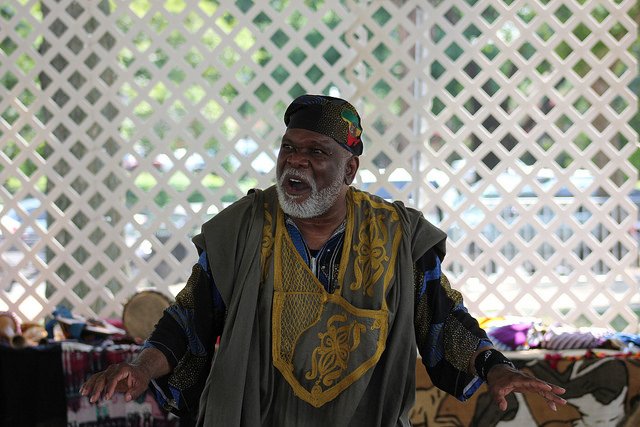

Photograph: ‘15.BabaC.Storytelling.Citified.46thSFF.WDC.5July2012’ by Elvert Barnes

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.