By Agatha Aduro

- Title: The Longing of the Dervish

- Author: Hammour Ziada

- Translator: Jonathan Wright

- Publisher: Hoopoe

- Number of pages: 297

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Fiction

What happens when you put a freed slave with strong leanings towards Jihadism and an impressionable, young, Christian nun, filled with a zeal to convert ‘African barbarians’, together in the midst of a Sudan that is embroiled in politico-religious turbulence? The result is what forms the core of The Longing of the Dervish, a novel by Hammour Ziada that in its Arabic original won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2014.

The novel is set in Sudan in the late 19th century, at the end of the Mahdist War. The Mahdist War was a British colonial war fought between Egypt and a part of Sudan led by a religious leader, the Mahdi, who fought for their independence. The Mahdi’s group was defeated after a long battle that left most of the fighters exhausted. Upon defeat, members of the Mahdi’s group were forced to flee the country. That war is also the focus of Rudyard Kipling’s The Light that Failed.

The story of The Longing of the Dervish begins at the end, or close to it. Bakhit Mandil has just been released from prison, to the streets of his native Omdurman, which is now engulfed in fire and smoke. ‘The holy city of Omdurman had been pounded by the shells of the infidels’ (p 1). Bakhit, a Mahdist, is crestfallen that their religious rebellion has been quashed, with the Egyptian infidels taking over. The shackles are off his legs but as later events show, they are still on his heart. ‘Bakhit didn’t feel he was free. Bad blood and revenge stood between him and freedom’ (p 2).

He has a list of six men he plans to kill in retaliation for the death of his sweetheart, Hawa. One by one, he eliminates his victims in a murderous rampage even as one of his intended victims sends men, led by another former Mahdist, to hunt him down. This prepares the ground for a conflict that leaves readers wondering what would happen eventually: if he would be caught, if he would go back to gaol, or if he would be killed.

The tale unfolds in the present with Bakhit going about his revenge while flashbacks provide the backstory, which relates to Hawa, who was originally Theodora. Theodora is a young Egyptian-born Greek woman who was dedicated to the Orthodox church by her father. She becomes a nun and later, after being convinced by a priest, a missionary to the ‘savages’ in Sudan. Theodora keeps a journal and has some literary pretensions. She describes herself as feeling like Shahrazad from the film Arabian Nights, as she arrives Sudan after a voyage with other missionaries and settles into the life of a missionary, teaching children and caring for the sick. She also spends time with her uncle and aunt, who seem to have taken very well to the country.

However, the Mahdist War breaks out, changing everything. The people are tired of their European overlords and follow the Mahdi, a man claiming to be divinely appointed by Allah to kick out the infidels. He quickly develops a following and civil unrest breaks out in various parts of the country. While many foreigners correctly read the signs of trouble on the horizon and flee the country, most of the Orthodox Mission and Theodora’s family choose to remain, lulled by a false sense of security.

Theodora is captured, sold into slavery and renamed Hawa. She is then purchased by a man who wants to use her to fulfil his sexual fantasies. It is in this new life that she meets Bakhit Mandil, the protagonist of the novel and the one through whom we follow the sequence of events that connect the past and the present. Bakhit falls in love with Hawa but though she seems to have some feelings for him, she has reservations and does not commit to him. Eventually, she is killed by her master when she tries to escape. Bakhit finds out and vows to avenge her death, but is arrested that same night. He spends the next eight years in gaol and is eventually released. At this point, the past meets the present and the rest of the plot unfolds in an intriguing continuation of flowery narration, Biblical and Koranic citations, and action.

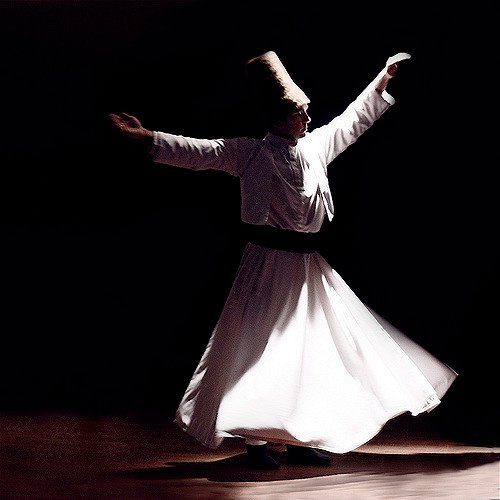

The Longing of the Dervish is a tale of ill-fated love, death and a quest for revenge. The book is divided into eighteen chapters that are further broken up into numbered sections. The story begins near the end and doubles back on itself. The narrative moves from the present to the past and back, sometimes within the same chapter and often in a way that the reader might at first find disconcerting but eventually gets used to. The narrative comes together at some point and progresses to a climax. Through this structure, the author creates a whirling feel to his rendition. The dance-like narrative can also be likened, at a deeper level, to the whirling or dancing of dervishes. A dervish is a member of a Muslim (specifically Sufi) religious order who has taken vows of poverty and austerity. The whirling dance of the dervish is part of a formal ceremony known as the Sama in which a dervish tries to reach religious ecstasy. The novel is written in the third person in prose that comes through in the translation of Jonathan Wright as a simple but poetic form of English.

In telling what is essentially a love story, Ziada touches on important themes such as race relations, faith, slavery, freedom and disillusionment. For example, in describing blacks, Dorothea, another nun that comes to Sudan with Hawa, and who is equally sold into slavery, says:

They smell horrible and rotten, like rotten fruit. And their sweat is poisonous. They don’t have the magic or the kindness of the Egyptians (p 84).

And about Bakhit, Theodora writes in her journal:

[He] was an example that the Western reader should be surprised to discover. Western literature ought to write about his changing ideas about love. He was like a lover from one of Shakespeare’s plays who had landed inadvertently in this savage country. If only he hadn’t been black. If only he hadn’t been a dervish slave. The worst mistake is to become attached to anyone in anyway, I don’t want to become like Bakhit (p 272).

The missionaries approach the Sudanese with the same superciliousness that has characterised these types of relations between whites and blacks. Perhaps, in response to this or as a form of balance, Ziada writes about Theodora’s beliefs and concerns in a cynical, almost mocking tone:

What made Theodora happiest was that she was able to have a bath in a closed room. Washing in the desert had been the most embarrassing, but in Berber the Lord had finally given her a mud-brick room where she could feel safe (p 99).

While it would be interesting to read the original novel, Shawq Al-Darwish, there is no doubt that the award winning translator, Jonathan Wright, does a good job in this English translation. His neat lines and flowery narration testify to the solid background that he boasts as a former Reuters’s reporter and translator of other notable authors like the renowned Alaa Al-Aswany, Yousef Ziedan and Saud Alsanousi.

The Longing of the Dervish is a book that tells a great story against the background of a significant period in Sudan’s history. Its major themes of loss, freedom and revenge make it universal. The focus on Bakhit also elicits some empathy from readers and shows the extents to which people will go for love, especially love that is wild. With the fine rendition by Wright, it is a book that will not easily be forgotten.

The reviewer acknowledges the support of Su’ur Su’eddie Vershima Agema in the writing of this review.

Photograph: ‘Mevlevi’ by kT LindSAy

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.