By Vuyo Mzini

- Title: The Forest Dames

- Author: AdaOkere Agbasimalo

- Publisher: Parrésia Publishers Ltd

- Number of pages: 303

- Year of publication: 2014

- Category: Fiction

AdaOkere Agbasimalo’s book, published in 2014 and titled The Forest Dames, is a fictional rendition of events that occurred during the Nigerian Civil War. A reader not resident in Nigeria (and not in touch with continental politics) may initially question the relevance of a depiction of a war from more than four decades ago. Scenes from the book, depicting Igbos fleeing from the northern part of the country to the South East, on account of being persecuted, seem far removed from the ‘woke’ culture of post-2010 consciousness:

The train spilled over with people looking harassed and frightened… They were on their way home. They had escaped from the killing in the city and were now trying to tame their fear.

The train moved on. The next station…fierce-looking men jumped into the coaches and pointed at some of the passengers.

‘You, you, you, come down’.

The men pounced on them, pulling them up forcefully and pushing them out. They never returned… Later, stories were told of how their heads were shattered with heavy iron rods, their brains spilling on the ground. According to the stories, their bodies were dragged to some location and, before long, vultures began to hover around (p 43).

Compare that to this account, based on evidence obtained by Amnesty International, of events in 2016, during the Biafra Remembrance Day on 30 May, some forty-six years after the end of the civil war:

Ngozi (not her real name), a 28-year-old mother of one, told Amnesty International that her husband left in the morning to go to work but called her shortly afterwards to say that the military had shot him in his abdomen. He said he was in a military vehicle with six others, four of whom were already dead. She told Amnesty International: ‘He started whispering and said they just stopped [the vehicle]. He was scared they would kill the remaining three of them that were alive… He paused and told me they were coming closer. I heard gunshots and I did not hear a word from him after that.’

A discerning reader will realise that Agbasimalo’s work is still of utmost importance in contemporary Nigeria and, in fact, the African continent as a whole.

The Forest Dames tells the story of how the women of the village of Nekede, in southeastern Nigeria, were terrorised by air raids and soldiers in the tumultuous time of the Civil War. While the terror afflicted everyone, it is Agbasimalo’s observation that ‘Men, women and children all eventually become victims of war but women always appear to be double victims’ (p 16). She shows this by telling the story from the point of view of Adaeze, or Deze as she is known, and her mother Dorati, called Dora.

Dora is a market woman who sells various products for profit in the city of Kaduna in the north of Nigeria. She is as industrious as she is resilient. In the wake of an attempted coup d’état, she and other Igbo women living in the region are confronted with evidence of retaliation against Igbos. When one of her fellow market women, Mama Gozi, is killed in her home together with her husband and five children, Dora and her husband decide to take their own children to their village home in Nekede. There they encounter food shortages and trading markets that are significantly distant and of scant supplies, on account of the government blocking inflows of resources into the region. Dora however is quick to rally the local women to find worthwhile markets in order to carry on trade that will help each household survive. Distances of over forty kilometres are traversed by foot in order to find supplies of ‘…rice, stockfish, tomato puree, salt, curry powder and even onions; items which the war had rendered contraband’ (p 78).

Throughout these journeys, the women have to contend with rogue soldiers, both federal and Biafran soldiers, who seek an opportunity to loot. At times the women are forced to return with no food for their homes. The problems explode when the village is besieged by air raids in which mortar bombs are dropped, maiming without discriminating. On one particularly long and gruelling market run, the women are taken by surprise by a barrage from the sky:

Before anyone could shout ‘take cover’, they heard ‘gboam, gboam, boom, boom, kpoom!’ One fast plane had dropped a string of lethal bombs as it whistled past the helpless traders who had already dropped their goods and were lying flat on the ground… The harassed women got up slowly…

‘Wait a minute,’ one of them shouted. ‘It looks like Liliana has been hit… There’s blood all over her, oh my God!’

Bits of Gonma’s mother’s flesh were strewn all over the ground. It was heart breaking and the women virtually rent their hearts.

‘Come, let’s drag her to a shrubby area and hide her there’, Dora urged as their tears streamed (p 79).

This scene marks the first in a series of gory scenes with bodies and severed limbs that require ad hoc burials in remote places. During a raid-induced exodus to a near-by village called Okolochi, a father and mother are forced to bury their fatally ill daughter in a shallow grave on the side of the road. A mother, running from Port Harcourt, arrives in Nekede village with only her son’s arm to bury. It is all harrowing, and Agbasimalo does not shy away from describing the gory details of dismemberment and trauma.

The abuse by rebel federal soldiers extends to the specific abuse and misogyny towards women and their bodies. The Forest Dames is a tale of how families and specifically the women in these families, coordinated their efforts to protect young girls from being abducted by rebel federal soldiers who do unimaginable things to them:

[The rebel federal soldiers’] favourite pastime was to hunt for and abduct young females or older ones in the absence of young ladies or mere girls, in the absence of either. They had no respect for females found within the invaded areas. They would not kill them. They would rather abduct and violate them (p 158).

Dora and Mrs Phoebe Ofoegbu, an elder in the village, coordinate for Gonma, Deze, Sofuri and Lele – all girls in their teens – to hide out in Mkporo Forest. While the forest is known for being home to wild beasts, the prospect of torture at the hands of the rebel soldiers leaves the mothers with no choice. It is here that the girls form lasting bonds and are spared the torment of being captured.

At the end of the war, Deze finishes her secondary schooling, goes on to study at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and is recruited into the National Youth Services Corps – a scheme set up by the Nigerian government to engage the youth in integration and nation building. Lele goes on to marry and have children. Not the man of her dreams, but a family nonetheless. Gonma moves to the UK and establishes herself in a new life with a Jamaican husband. All relatively ‘ok’ endings given the horror each of the women had to go through.

The point of Agbasimalo’s work is summarised succinctly in the foreword to the book, delivered by Chief Justina Anayo Offiah SAN, ‘This [work] is expected to evoke a candid self-admonition and consequent resolve to opt for peace and stability in the world’ (p 14).

The book does this very well. It especially does a brilliant job of capturing the traumas that may be considered ancillary to the incendiary gunfire and massacre of frontline fighting: the impact of the food restrictions and supply blockages on child mortalities as a result of the kwashiorkor disease; the post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by mothers receiving back only the scent of their sons from boots delivered by survivors; the postpartum depression of women who birth children conceived through continuous and multiple rapes.

The persistence of warfare through the years – the insistence of human beings on engaging in and inducing war – is puzzling and worrying in the context of all the warnings that have come down through the years. In 1920, a wartime poem was published, written by the English poet Wilfred Owen, called ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’. Owen takes the title from the Roman poet Horace, who established the full Latin phrase, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (it is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland), as the words that could raise those fallen in war to hero status and motivate others to sacrifice themselves as well. In his account, Owen calls the Latin phrase ‘the old lie’, and in the second stanza he describes an unattractive scene of a haggard bunch of soldiers scrambling for their lives on a battlefield:

Gas! Gas! Quick boys!

An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time.

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

It is scenes like these that make it worth repeating that Agbasimalo’s work and message are of utmost importance if we are to learn from the past and avoid the drumbeats summoning contemporary Nigeria to war. Because war, friends, is good for absolutely nothing.

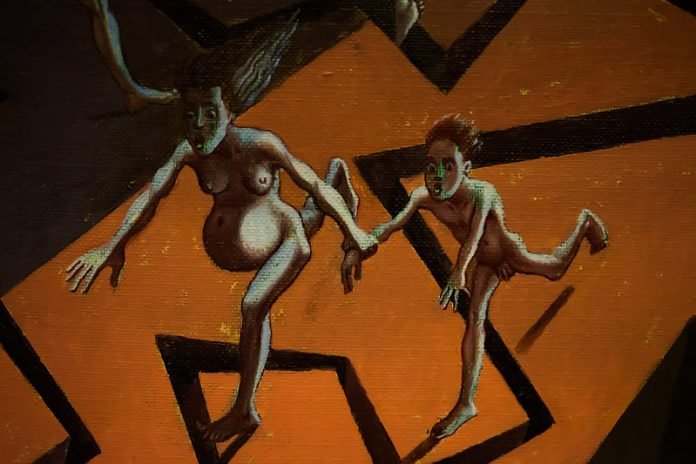

Photograph: ‘Fled’ by Thomas Hawk

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.