By Ekemini Pius

- Title: Den of Inequities

- Author: Kinyanjui Kombani

- Publisher: Longhorn Publishers

- Number of pages: 188

- Year of publication: 2013

- Category: Fiction

Den of Inequities is a subtle satire that interrogates the problems of Kenyan society, just like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s excellent novel, Wizard of the Crow. Kinyanjui Kombani weaves this story around the lives of three characters – Omosh, Gosti and Aileen – through whom we are made to understand the lives of the ordinary people of Nairobi and the failure of the Kenyan government on different levels. One reason Kombani deserves a lot of praise for this historical novel is because this is exactly the kind of blazing attack on the government that forced Ngũgĩ into exile when Kenya was still under a dictatorship. Even though this novel was published in 2013, when Kenya had transitioned to a democracy and writers who criticise the government are not persecuted as fiercely as before, it takes some guts to attack a powerful government with literature.

Omosh is a middle-aged man who works at construction sites to cater for his family. But the weekly wage he receives is not enough to make his family comfortable, and he falls into a series of debts as a result, including house and shop rents. His son is diagnosed with pneumonia, contracted from exposure to cold due to their squalid accommodations, and he has to buy a very expensive drug for the boy to survive. With no hope of raising the money, he meets the foreman at the construction site and threatens to commit suicide if he is not paid his wages in advance. The foreman takes him seriously and pays him his wages for the subsequent weeks. He buys the medicine and hurries home. He meets two men fighting on his way, and as he stands to take in the scene, policemen arrive at the scene and arrest him and the two men who were fighting. The two men manage to bribe the officers and are released, but Omosh does not have money, so he is bundled into the police vehicle and subsequently thrown into a cell, despite his pleas that his son will die if he does not take the medicine home. While in the cell, he is forced to adapt to dehumanising conditions: dirty floors and walls, measly food, sexual molestation. It is at this point that Kombani begins to subtly make his point about the evils of the detention system, a theme he explores fully as the novel progresses. When Omosh is finally released, after serving three months of hard labour, he hurries home to discover that his wife has married another man. Things rapidly slide downhill from this point.

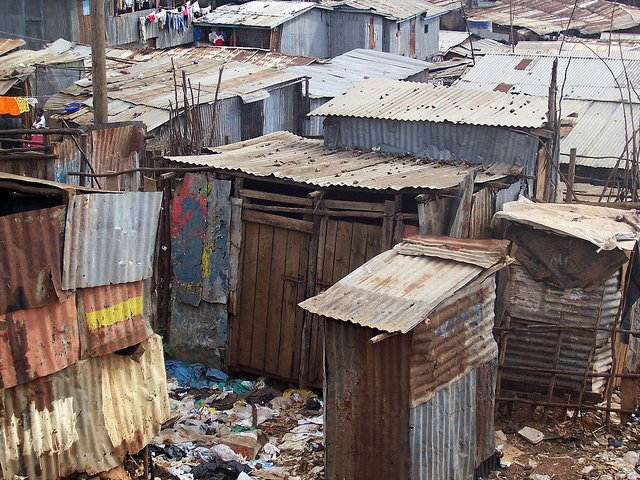

The character of Omosh is very significant because through him, we can see how ordinary citizens are abandoned by a government that is supposed to protect and uplift them, so much that they descend to the bottomless depths of poverty. Their environment becomes a slum, the home of every conceivable crime, from bag snatching to rape. The problem with slums is that governments do not prioritise them, so they descend into crime and dysfunction. Through the character of Omosh, we also see the corrupt nature of the Kenyan Police Service, with the police arresting people indiscriminately and taking bribes from them in return for not making them face the horrors of the cells. The Mashimoni slum is hell because the Police Service, which is a microcosm of the government, has failed woefully, thereby emboldening the criminal elements that thrive there.

The second character, Gosti, is a criminal in Mashimoni. He was abandoned by his father at a very tender age, and in the struggle to survive, he learns the art of shortcuts and brute force. Gosti is reminiscent of Fofo in Amma Darko’s Faceless; both characters are left to the mercy of the streets. But whereas Fofo somehow finds a way to unlearn the life of the streets, Gosti is not so lucky. He has been arrested so many times and thrown into the police cell so consistently that he has his own bed in the cell. His father shows up later at the police station when he is arrested for murder and promises to free him if he agrees to help him kill some people. Through Gosti, we see what detention does to a man. The police cell, which is like a mini prison, hardens Gosti by reinforcing everything he has had to live with in the slums: deprivation, violence, mutiny. Kombani brilliantly shows how the detention system is designed to deliver the coup de grâce on already dehumanised people, such that its stated purpose of deterrence is defeated. This is why Gosti is not scared to rape women and snatch bags; he knows there is nothing the detention system will do to him that the streets have not already done. Gosti is a reminder that parents should never abandon their children, because parental upbringing is vital in shaping their lives and instilling values in them that can help them resist the lure of social vices. Kombani uses Gosti to pass across a salient message: unless the slums are fixed, products of the slums should not be put in detention because detention is just an annex of the slums, with free food, albeit measly, and freedom from threatening landlords.

The third character, Aileen, is a model and a student at the University of Nairobi who is very popular as Miss Campus. She is also very rich: her father is a Minister and member of Parliament in Kenya. Through her character, we see how the government, represented by her father, neglects the University of Nairobi. The character of Aileen enables us see the failure of government in another shimmering light. Her father sends her to a federal university that is supposed to provide quality education and accommodation for all students. But he is not bothered by the the fact that many students cannot afford decent accommodation; he is only interested in ensuring that his daughter has the best possible accommodation. This display of selfishness is symbolic because it is what African leaders actually do all the time: embezzle money meant for fixing roads while potholes bury commuters daily; stash money in Swiss accounts while someone dies at the General Hospital because there is no syringe to inject them with.

Aileen dumps her boyfriend, Alex, for Edward, a young man who helps her out when she is almost thrown out of a matatu for losing her transport fare. Unknown to her, Edward is the leader of a militant group called The Chama. This group is against Westernisation in all its forms, and even has highly placed government officials as members, including Aileen’s father. The members of this sect are so difficult to apprehend and neutralise due to the fact that they have informants within the government. The police have been searching for them and finally round them up by going on a campaign of extrajudicial killings. This is the thrust of Kombani’s novel. Kombani is of the strong opinion that extrajudicial killings are against the rule of law and the tenets of democracy. Extrajudicial killings undermine the power of the judiciary, because they indirectly imply that the judiciary is not capable of effectively handling criminal cases. It also goes against the principle of justice, for justice can only exist in a state where alleged criminals can stand in court and defend themselves.

Photograph: ‘The Kiberia Slums in Nairobi Kenya’ by Christine Olson

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.