- Title: And after Many Days

- Author: Jowhor Ile

- Publisher: Kachifo Limited

- Number of pages: 287

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Fiction

Family is beautiful, an institution of love that binds more than mere friendship when genuine love is present. Family is not just a group of individuals who live together – the fraternal love and amity between siblings is wonderful when it is present. And, to be fortunate enough to have people who can be regarded as relatives is to be blessed immensely.

In his characteristic manner, Kurt Vonnegut, some of whose stories centre on family, the value of kinship and life, writes about his experience of a Nigerian family in the introduction to his quirky little book, God Bless You, Dr Kevorkian:

I met a man in Nigeria one time, an Ibo who had six hundred relatives he knew quite well. His wife had just had a baby, the best possible news in any extended family. They were going to take it to meet all its relatives, Ibos of all ages and sizes and shapes. It would even meet other babies, cousins not much older than it was. Everybody who was big enough and steady enough was going to get hold of it, cuddle it, gurgle to it, and say how pretty it was, or handsome. Wouldn’t you have loved to be that baby? (p 12)

In this sentimental passage about copious family and love, we see that the idea of family is not limited to the immediate. We also see that there is a sense of belonging and care that is about the joy of kinship.

Family is also a complex structure. There is something indefinable about familial union, and only a good story can bridge our understanding and that which is often otherwise impossible to fully apprehend. This is what Jowhor Ile’s debut novel, And after Many Days, tries to do.

Likewise, the love that develops between siblings in their childhood gifts them with compelling memories. Occasionally, when we are awash with memories from our childhood, a state to which And after Many Days was able to continually bring this reviewer, we are fortified by those memories and something wells up in us that cannot be easily explained.

On the theme of family and love among siblings, And after Many Days put this reviewer in mind of Chigozie Obioma’s critically acclaimed The Fishermen, and some parallels can be drawn. The story in And after Many Days is narrated by the youngest of the siblings, Ajie, just like Obioma’s Benjamin. The two novels subtly engage, as a socio-political backdrop, Nigeria as well.

Set in the city of Port Harcourt, And after Many Days is the story of the Utu family: Bendic, Ma, and their children, Paul, Bibi and Ajie. It is the story of the coming-of-age of the Utu children, set against the backdrop of Nigeria in the ‘90s, a period of military dictatorship, political upheaval and the doldrums of the oil economy. The narrative centres on familial bonds, loss, community struggle and bereavement.

On a Monday morning that could have been just any other day, after a quick shower, Paul, the eldest of the Utu children, leaves home for the house of a friend, in the neighbourhood. He does not return, throwing his siblings and parents into panic and confusion:

Paul floundered by the door as though he had changed his mind; then he bent to buckle his sandals, slung on his backpack, left the house, and did not return.

At least this is one way to begin to tell this story (p 9).

It is strange how a change in the simple routines of our daily lives can complicate many things about us: our beliefs, our inner cohesion, our faith in others. In And after Many Days, Paul’s sudden disappearance raises the question of fate. His disappearance becomes the unforgettable event. Of course, as humans, we always connect our sad events with other sad events that may not touch us personally. And, in fact, there are other unpleasant events that the Utus associate with their loss:

It was the year of the poor. Of rumours, radio announcement, student riots, and sudden disappearances. It was also the year news reached them of their home village, Ogibah, that five young men had been shot dead by the square in broad daylight. The sequence of events that led to this remained open to argument (p 10).

Paul is searched for, reported missing to the police but nothing comes up. The Utus are in limbo about his whereabouts: whether he is dead (at least they would have his remains to bury), kidnapped, or just gone of his volition. In the end, they submit to their kismet and move on with a hole in the family. There is a Yoruba saying that translates as, ‘It is preferable that one’s child be dead than lost’. The reason for that saying is the agony and enervating uncertainty that taunts the heart of parents of lost children that is worse than having to bury a dead child, once and for all.

Using flashbacks, the story explores the history of the Utus, ostensibly in a bid to help the reader grasp or find a clue to Paul’s disappearance, the supposed conflict of the main plot. The flashbacks unfold manifold memories of the narrator’s childhood: how the father, Bendic, earned that name – the way Paul said the name Benedict when he was learning to talk. Bibi and Ajie would follow their elder brother in this practice. In Nigerian society, at the time in which the novel is set, it was even less common for children to call their parents by their first names. The children’s Auntie Julie scolds them for it. She considers it rude, and considers the parents’ passivity to be negative reinforcement. This issue is one of the ways in which the author shows the freedom enjoyed by the children of the Utu household.

Paul is at an impressionable age, and he is influenced by the societal and political happenings of the time. Often, he explains many things of this nature to his sister, Bibi, and his brother, Ajie, who are almost always squabbling. This is the author’s method for handling socio-political commentary. When the children visit their hometown, the narrative introduces the reader to the nature of early disputes over oil exploration within the communities that would go on to play hosts to the oil companies. Their father is saddled with the responsibility of playing the mediator, commanding the respect of members of the community because he is educated. At this point in the book, the continuity of the plot is largely lost, like a long digression rather than a contribution to the main plot.

Eventually, the narration returns the reader to the main plot. News comes about Paul, after many years, when the family has given up hope and moved on, and the news is such that it leaves them astounded. The event of fatality is clearly not well handled in the denouement, like glue meant to hold strands together but which fails. It causes the whole plot to come undone, for in taking the reader back, the author acknowledges having neglected the initial account.

There are minor themes, of communal struggle against environmental pollution and degradation, in which the government and multinational companies are complicit; police irresponsibility and brutality; religious fervour and political corruption. The struggle against the military oppression of that period is evident in the novel’s reference to the late writer and activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and other activists:

The nine Ogoni activists who were detained for over a year by the military government were recently tried, and a few days prior, the Provisional Ruling Council announced it had approved their execution. The news sent everyone reeling (p 252).

Jowhor Ile writes with a sensitivity that will surely endear many readers to him. His characters are gracefully drawn. They are not just names in a book; the story gives them life. And many a reader will recognise similarities between their childhood and that of Ile’s main characters. Also, Ile’s effort in recreating the ‘90s with evocative descriptions and well-chosen detail is laudable. The description enlivens the story, sets the mood.

The novel is a commendable debut but not without its flaws. The author is not a disciplined storyteller. There are authorial intrusions that quarrel loudly with the narrator’s voice. There are descriptions, out of place, superfluous and excessive, and there is nothing to indicate that they are hallmarks of great style; there are other authors, for example Amy Tan, who can pull off this kind of thing. It is just that this author drowns in the flow of his own narration. He loses the plot, as they say, and that leaves a rather poor impression of his storytelling. The freedom of descriptive power in prose should neither be abused nor taken for granted.

That And after Many Days won the 2016 Etisalat Prize for Literature is another indicator of the promise of the author and his work. It is this promise that Binyavanga Wainaina sees when he declares that ‘Nigeria has a new star’.

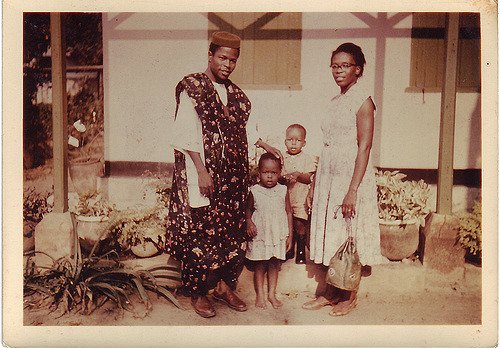

Photograph: ‘Family’ by J Mark Dodds

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.