By Ofuonyeadi Chukwudumebi Mercy

- Title: My Africa, My City: An Afridiaspora Anthology

- Editor: Nana-Ama Kyerematen

- Publisher: Winepress Publishing

- Number of pages: 155

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Essays, Fiction, Poetry

In his collection of essays, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o writes, ‘Language carries culture, and culture carries, particularly through orature and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in the world’. English, acquired from European colonisers, has become a tool in bridging linguistic barriers between Africans. Chinua Achebe said in his essay, ‘The African Writer and the English Language’, ‘I feel that the English language will be able to carry the weight of my African experiences. But it will have to be a new English, still in full communion with its ancestral home, but altered to suit its new African surroundings’. In this light, English as used in African literature is not just what was bequeathed to us but a new Creole capable of relating the African experience.

Edited by Nana-Ama Kyerematen, My Africa, My City: An Afridiaspora Anthology is an anthology of ‘new voices’ who share their ‘collective experiences as Africans’ using English as a medium. It explores the post-colonial or cotnemporary scene, the better to appreciate changes in metropolises that are ‘energetic, vibrant, and full of life’. Kyerematen is the founder and managing editor of Afridiaspora.com which encourages, mentors and publishes emerging writers. The anthology includes short stories, poems and essays by twenty-seven writers, including South African poet and short story writer, Abigail George; Kenyan digital novelist, Alex Nderitu; Nigerian medical doctor, poet and writer, Dami Ajayi; Liberian writer, Hawa Jande Golakai; Nigerian poet, pianist and writer, Echezonachukwu Nduka; Nigerian poet and writer, Jumoke Verissimo; and Motswana poet, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami. Collectively, they bring to life various issues peculiar to Africa and its people, with references to specific places.

One of the themes explored in the anthology is class, which cuts across people from all walks of life. In a world characterised by segregation, economic power is a vital prerequisite to belonging to the elite. This is reflected particularly in Taonga Zulu’s ‘Ponte’. The poem depicts a society that is segregated not only economically but also socially. Each stanza refers to a new group of people, notably the poor, characterised as ‘men of the walkway’, and the rich, identified by ‘humble castles of previous rule’. However, the beauty of the city, in this case Johannesburg, South Africa, is clearly defined by the synergy between both groups. The poet does not deny the fact that there is a dichotomy but he lauds society’s efforts to live in harmony. In the closing lines, he describes the city thus:

I come from a city

of both laborious work and glorious fun

that mosaic of a metropolis

Where Ponte rises above the horizon.

Frances Ogamba’s story, ‘The Thing about This Place’, centres on the cost of living in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Nero, a young man who lives in Lagos, decides to spend his leave with his sister who lives in Port Harcourt and who recently put to bed. While in the city, he attends a reunion with friends at the Presidential Hotel which leaves him in shock as he comes to understand that the city only offers succour to the wealthy. For instance, the beggar in the story will forever remain a beggar.

Another theme explored is the hustle and bustle in Africa. Bolaji Olawale’s poem, ‘Life in Pictures’, explores the frenzy of Lagos where people from all walks of life intermingle in their quest to make a living. In the process, he directs the reader to other aspects of the city, especially those rarely talked about, like the aspect that comes to light ‘on a Monday evening, where life will rip off her buba, like the irrational woman she is’.

Multiple relationships is yet another theme in the anthology. Joshua Omena’s ‘The Concubines from Jos’ portrays the poetic persona in various ways to his lovers: Bukuru, Rukuba, Lamingo, Shere, Terminus, Rayfield and Zawan. Each stanza is dedicated to one lover and tells why he loves her. There is no gainsaying that African cultures are largely polygynous; men are permitted as many lovers or spouses as they want. The names of the lovers are also the names of residential and commercial areas in that Nigerian city.

The theme of ethnic pride is evident in Alex Nderitu’s ‘Everyone Knows a Kamau’. The poem adequately reiterates the importance of home, where everything is familiar. There is also a political undertone concerning loyalty to one’s nation. The poet is optimistic about his country. Even though he knows that many cities in Europe are far more developed than Nairobi, Kenya, he still appreciates what his city has to offer.

Dami Ajayi’s ‘The Lagos Everyman’ describes the traffic in ‘the Lagos rush hour’. Like Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam, in Diana Nyakyi’s ‘Forget about a Chicken’, the ‘go-slow’ is intense as it is guided by ‘the theory of Traffic Disequilibrium’. In Ajayi’s story, there is a troublesome older sister, Titi, who has a corresponding character in Lulu of ‘Forget about a Chicken’. Both stories explore the lives of two working-class men, one married, the other a struggling bachelor who is pushed to live elsewhere by his sister’s ‘caustic tongue’.

Echezonachukwu Nduka’s essay focuses on the meaning of the Imo State government’s vanity project, the fancy site Freedom Falls, in Nigeria. We are told that it means something to the government that built it and also to the people who take pictures in front of it, probably seeing it as a tourist site. For the builders, it is supposed to portray a clear insight into the workings of the administration. To that government, the site is a historical statement, as suggested by its name.

An important takeaway from this anthology is a sense of the unique African way of writing, poetry especially. African poetry pays scant attention to rhyme or metre and is more concerned with passing on a message. Taken as a whole, the anthology succeeds in its aim of giving ‘new voices’ from different parts of the continent a platform to share their experiences. It also succeeds in exploring the social, political and economic aspects of life on the continent, even though it ignores the role of tradition in the lives of the people. It is true that the perception of Africa today is of a modern-day metropolis but this is not so for a large percentage of the population, who still live closer to the lives – and therefore, the cultural values – of their forebears. This anthology will not satisfy readers yearning for the Africa that existed before it grew to be what it is today.

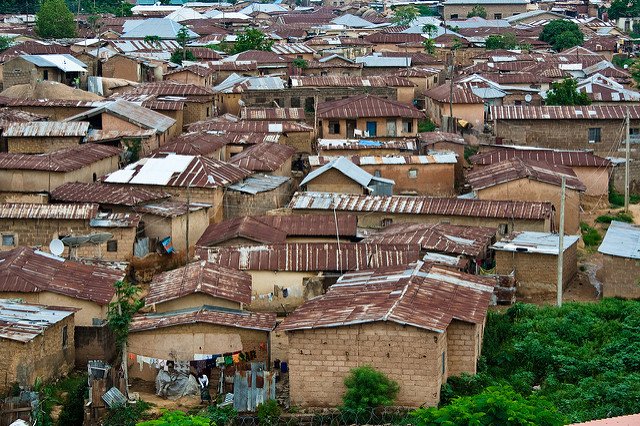

Photograph: ‘Jos’ by Andrew Moore

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.