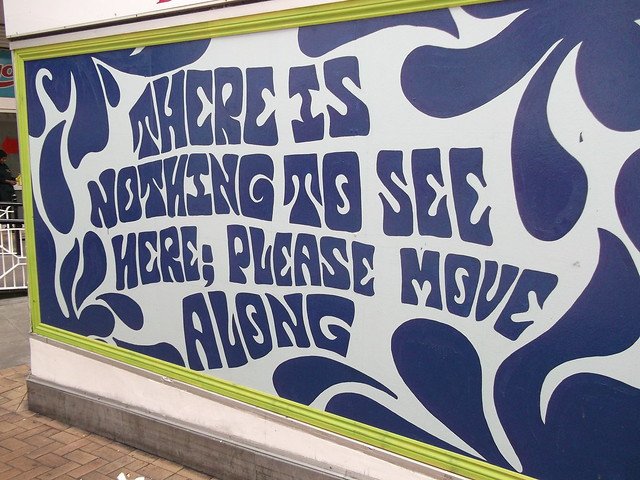

- Title: Nothing to See Here

- Editor: Hilda Twongyeirwe

- Publisher: FEMRITE Publications Limited

- Number of pages: 283

- Year of publication: 2015

- Category: Fiction

Nothing to See Here is an anthology that comprises sixteen short stories by sixteen African women writers. One can think of it as a box containing cupcakes of different flavours, with the flavours representing the different subject matters addressed by these stories. The icing on these cupcakes is the biographies of the authors at the end of the book. The bird perched on a wire on the book cover depicts the perspectives of not only the writers as they address certain issues but also of the readers as they perceive these stories.

Contrary to the title, there is everything to see in this anthology of the fifth FEMRITE residency for African women writers. Moving from East Africa through South Africa to West Africa, the anthology deals with stories revolving around identity crisis, racial favouritism, feminism and womanhood, domestic violence, childhood, depression, corruption, class stratification and so on.

Racial favouritism by American multinationals and non-governmental organisations in Uganda is addressed in the opening story of this anthology, Melissa Kiguwa’s ‘Always the Head’. This favouritism is cleverly done, as the locals are made figurehead directors whilst their American counterparts get alarming, off-the-record benefits which the former know nothing about. It is important to know the ways in which cultural power structures rate one’s body and experiences as valuable, because this is done at the expense of others, just as the main character, Solome, says. On the bright side, this is an issue that can be tackled systematically, unlike matters of the heart. When smitten with someone, there is a high tendency of giving one’s all and loving blindly with one’s heart. But for one’s emotional safety and mental balance, the story advocates that one should always think with the head. Here, Solome’s mother says to her, ‘If I followed my heart, we would not be where we are. It is always the head, Solo. Always the head’.

Is there really an acceptable excuse for domestic violence? When is the right time to flee from an abusive spouse? In the face of infidelity, frustration and fear, should a woman still be willing to stay through thick and thin? These are the questions that linger in this reader’s mind after reading Monica Cheru-Mpambawashe’s ‘My Fault’. The protagonist says:

It was not as if Ray beat me up all the time; it had only happened about fifty times in three years. Anyway, most of the times it was just mere slaps. The real bad ones were only four really. And it was not as if he was a bad man. He was a good father and he often made me laugh.

She further admits that, ‘…it was not as if I had not known that he had a volatile temperament before I married him. It was his unpredictable nature that attracted me’. Regardless of the emotional attachment that a person may feel towards their partner, there should be no excuse to remain in a toxic relationship. It is common to force the ‘endurance is key in any marriage’ speech down the throat of an African woman. But be it friendship or a romantic relationship, no ‘-ship’ is worth losing one’s mental or emotional stability over. There is a limit to which a woman should endure in her marriage. Physical or verbal abuse should be a deal-breaker.

In ‘People of the Valley’, the writer, Makhosazana Xaba, adopts a different style of writing which does not go unnoticed. She introduces the reader to the culture and mindset of the town in which the story is set by writing in radio programming style. The protagonist, Thulisile Thabethe, a radio presenter, uncovers stories that do not usually appear in news headlines. Listeners call in to air their views on the stories, sometimes switching from English to Xhosa. To retain the weight of the code mixing and code switching, the writer does not translate some parts to English. The story ends with a cliff hanger, successfully leaving the reader yearning for a follow-up. Who would not want to know how the case of Matron Langa, an accredited midwife in whose possession a freezer full of babies’ placentas was found, ends? The reader is eager to hear the matron’s side of the story.

Grace Neliya Gardner’s ‘The Sausage Tree’ leaves the reader to justify the role of tradition in child bearing in an African society. Does the main character, Mazuwa’s situation validate superstitious beliefs as a reality or is it just a mere coincidence?

‘Reconstruction’ by Doreen Anyango reminds us to always check on those who seem strong and to have it all together because they may be secretly suffering from depression. In the story, Donald overdoses on a concoction of drugs. He leaves a note saying, ‘I can’t do this anymore’. In Lauri Kubuitsile’s ‘The Do-Gooders’, Rene’s mother’s ‘black mood’ costs her her family, as they never live with her again.

Noticeably, most of the stories in Nothing to See Here are didactic. It is inferable from Mercy Dhliwayo’s ‘The American’, that one should always be content with what one has at the moment. However, this is in no way condemning one’s desire for better or search for greener pastures. But comparing one’s standard of living to that of another person could lead one into making hasty and irrational decisions.

The environmental description in Bolaji Odofin’s ‘Happiness’ is fascinating and detailed. ‘A blue star is born, water ripples in a pond, a cloud drifts by, a leaf bends in the wind’ are some examples. At some point, the reader forgets that the characters in the story are not even human beings, but different breeds of cats. These cats are invested with human traits such as talking, which makes the story stand out. The underlying message is that happiness is worth more than the unending stress on humanity.

Hilda Twongyeirwe provides insight into the undisclosed happenings in the political realm and addresses the embezzlement of public funds by government officials in ‘Baking the National Cake’. She writes:

The VP took his mistress on a shopping spree in London. When it was discovered that all her expenses were paid for by tax payers’ money, the VP asked David to quickly dispel the rumour by creating a ghost VP from the Office of the President who supposedly traveled with the VP.

The story serves as an exposé of political charlatans. It has become visible to the blind and audible to the deaf that majority of those that contest for one public office or the other have the aim of amassing wealth if elected. Rather than help bake the national cake, that is, build the nation’s economy, they yearn for a slice or share of it. If only these leaders put the same energy and enthusiasm they use in spending government money on personal escapades, into nation building, the imaginary Kabira would be a better place.

In a bid to change the narrative of the society in which they find themselves, these African women writers infuse humour, dreams and aspirations into their stories. They are redefining their stance by exploring topics such as education and independence, as well as reflecting on age-long conventions, such as what women do when faced with spousal abuse. The protagonist in Cheru-Mpambawashe’s ‘My Fault’ holds high the flag of perseverance; she says:

It was up to me to make sure that I did not enrage him so he would not have to lay a hand on me. If I kept my stupid tongue in check instead of nagging him, he would be the most angelic of all men. So, how could I go to the police and report when it was my fault?

Nothing to See Here offers variety on one plate. There is something about the panache of the different styles adopted in each story. The African languages used make one not bother too much about understanding everything. By creating a blend of cultures, it gives the reader a wide scope of experiences to explore.

Photograph: ‘Nothing to see’ by Tim Ellis

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.