By Kemi Falodun

- Title: The Book of Memory

- Author: Petina Gappah

- Publisher: Cassava Republic Press

- Number of pages: 311

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Fiction

‘Blessed are the forgetful, for they get the better even of their blunders’, wrote Friedrich Nietzsche. For some people, forgetting is a defense mechanism against unwanted memories, a way to avoid pain: the one they were subjected to, the one they caused others, or both. For others, being involved in different activities may suppress, or at least help them cope with those unwanted memories. But what recourse is there for one who is imprisoned and has nothing more than silence, time and memories? How does such a one run from their past?

In Greek mythology, Mnemosyne is the goddess of memory and mother of the nine muses known as the personifications of artistic inspiration. However, Mnemosyne, the narrator in Petina Gappah’s The Book of Memory, was a child who endured verbal and psychological abuse at home and in school for many reasons, especially her albinism. Now she is a woman serving time in Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison in Harare, following her conviction for the murder of a rich white man named Lloyd Hendricks. As part of her appeal, she is told to write down everything she remembers relating to the events that led her there.

Memory and Mnemosyne are used interchangeably in referring to the narrator. Being in a physically confined area does not hinder her from showing the readers her past and the present. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that the knowledge the reader has been given is questionable because not everything the narrator thinks she knows to be true is in fact true. This leads to the age-old question: how reliable is the human memory? As it is with recollection, each act of remembering alters the former such that, one realises that after two years in prison and much rumination on the past, what Mnemosyne records may not entirely be the truth. Upon realising that the particular incident she anchored her life on was in fact misinterpreted, she asks, ‘How do you begin to understand your life all over again?’

In this book, Gappah explores the themes of love, trust, friendship, resilience, family, fatalism, dreams and wakefulness, the nature of memory, and what it is like to be considered an outcast in a society. The book shows the disdainful treatment albinos are subjected to in some societies, ‘For the first time in as long as I could remember, I prayed for something other than dark skin; I prayed for a tambourine of my own’ (p 129). It may appear innocent and sincere, but this singular sentence is also a truckload of sadness and loneliness. Why would a child be burdened so much by cares of how she looks? Assimilation is not a concept Mnemosyne is familiar with as a child, so when another world, provided by Lloyd, her adopted father, presents itself as warmer and more welcoming, she gradually allows herself ease into it. In this grand house, she discovers books; to her, they are other worlds to disappear into.

Lloyd and Memory have a complex relationship. Despite belonging to different races and socio-economic classes, it is their private struggles with a lack of acceptance – although depicted in different ways – that unite them. When Memory learns of Lloyd’s secret, out of jealousy and immaturity, she handles it tactlessly. This makes their relationship fall apart.

Memory writes, ‘I wondered why Lloyd had taken me in. You see how insidious his influence is, how I am using his language’ (p 160). This is a testament of how a person’s life may affect another’s, but it can also be regarded as a pointer to the gradual obliteration of a people’s language after the arrival of colonialism. The narrative functions on more than one level.

The book is set against the backdrop of the political unrest in Zimbabwe and its impact on individuals. The writing contains vivid descriptions as they appeal to the senses, interspersed with a Zimbabwean demotic and doses of humour. Despite the importance of the story, the first half of the book manages to drag. The reader sees the narrator’s frustration but does not feel it, leaving the reader’s desire for a richer portrayal of the narrator’s inner life unfulfilled. Granted, the narrator has mostly kept to herself all her life. Nevertheless, the narrative does not provide sufficient access to her thoughts.

There is a powerful exchange that can easily go unnoticed by an inattentive reader. Memory’s sister, Joyi, has a burn scar. However, in telling a classmate about it, Memory claims the scar as her own. This sororal context serves to further emphasise the importance of telling one’s own story. Otherwise, strangers will come into one’s house and leave with whatever narrative they want and may even claim some parts of it as their own. The Book of Memory shows what happens when one’s experiences are viewed through other people’s lenses.

Another thing worthy of note is the skilful way Gappah addresses issues that many authors shy away from. One of such is the role of the artist and the impact of their work in shaping the narrative of a people. The reader encounters interesting characters such as Zenzo, a Zimbabwean artist who finds his way to Europe and tells everyone he is on exile. He revels in the attention his work receives and puts himself forward as the voice of the people. One of his reviewers describes his work as ‘evocative images of tortured homeland’. But the reader soon learns that:

None of it is true, of course, but who cares for truth when there is a troubled homeland and tortured artists to flee from it? The more prosaic truth is that he did not flee, but rather left on the arms of his German girlfriend (p 206).

Gappah does not take lightly the topic of representation. ‘I don’t see myself as an African writer’, she said in an interview with The Guardian in 2009. ‘It’s very troubling to me because writing of a place is not the same as writing for a place. If I write about Zimbabweans, it’s not the same as writing for Zimbabwe or for Zimbabweans’.

There are series of revelations in the story followed by the familiar package of trauma and death. Yet, the ending of the book offers hope, not only about Memory’s future and the possibility of freedom, but also about her reconciliation with her past.

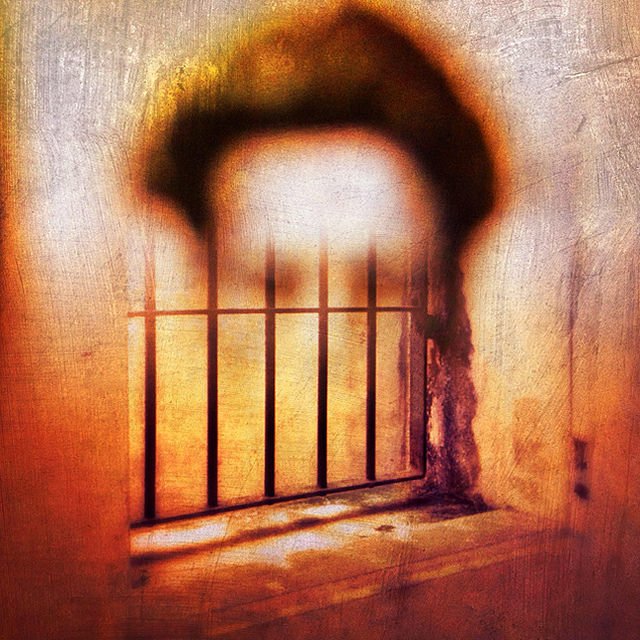

Photograph: ‘Memory Fade’ by Kurt Norlin

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.