- Title: King of the Jungle

- Author: Bizuum Yadok

- Publisher: Kraftgriots

- Number of pages: 271

- Year of publication: 2014

- Category: Fiction

The path of one’s life is inscribed on one’s palms. It is not in the crooked lines but in how such a person decides to use their palms: to work, to be soothing or to be violent. This largely goes to say that the fate of everyone lies in the decisions they make. This principle underlies the tale that is Bizuum Yadok’s King of the Jungle. King of the Jungle is a tale seen through the eyes of two brothers. The author brings the nature/nurture question to the fore in this work, highlighting in great detail the birth and growth of the two brothers and what they become.

We meet Giwa at the beginning of the novel: an intelligent student who wins all the prizes at his secondary school graduation. There is a waiting period between his graduation and admission into the university. In this time, Giwa stays with his uncle and his cheating wife. Giwa then goes to stay with his mother in the village. The village changes Giwa into a local champion of sorts as he begins to keep bad company, loses his morals and becomes proud. Much later, he gains admission into a university, where he gets involved in drugs, cultism and murder. All these slowly tilt Giwa’s story towards tragedy in a way that will leave most readers thinking deeply.

The story of Solomon Tambes Bakka, Giwa’s half-brother, runs in parallel to Giwa’s story till when their tales converge. Solomon lives a really rough life, raised by missionaries and priests. He struggles to find his bearing in society and get an education despite all the evil life throws at him. The two brothers have no idea of each other’s existence till fate brings them together. While Giwa goes the way of crime, Solomon becomes a crime-fighter. The paths both of them take become the deciders of their destinies.

Yadok uses the omniscient point of view to tell this tale. The author takes readers back and forth, in time and across space, to learn several backstories that help to build the sequence towards the denouement. While the drug-related, cultic and violent scenes give the novel the feel of crime fiction, the sections set in the village, the names of characters and the nuance of the narrative give it a distinctive African feel.

The strength of the book lies in the breadth of its thematic coverage, which includes family, friendship, loyalty, the role of education in life, poverty and the struggle for existence. Indeed, there is a strong sense of poverty and the struggle for existence that runs through the pages. Giwa and Solomon wrestle with the evil that leads many men to their doom. Giwa’s turn to drugs and cultism stems from his desire to have a means to support himself through school while providing for his sister.

Religion is portrayed as a strong force that shapes people. Solomon is raised by the goodwill of religious people, from priests to kind-hearted, fellow Catholics. In King of the Jungle, certain people find peace through true religion and peace with Jesus. This is exemplified by Hannah, who was once Giwa’s girlfriend. Like Solomon, she becomes a staff of the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) and is one of the NDLEA staff who preach salvation through an acceptance of Jesus. This group of staff, called the ‘Second Chance Officers’, are encouraged by the NDLEA, like many other people and institutions that encourage conversion to Christianity for their ulterior motives:

Activities of the Second Chance Officers were encouraged because most of the repented souls freely confessed and volunteered useful information to the NDLEA (p 262)

Corruption and hypocrisy are also portrayed in their many facets. One of Solomon’s guardians, Fr Kut is portrayed as a womaniser who sleeps with ‘a divorcee who had recently become a nocturnal visitor’ (p 76). The author notes that:

Father Kut was getting incredibly bitter. Solomon observed a protrusion at the front of father Kut’s cassock, he then understood what he meant by ‘wasting my time’ and the need for him to be as brief as possible so he hit the nail hard on the head (p 76)

That scene also captures the humour that underlies some of Yadok’s descriptions while also pointing to the presence of clichés (‘hit the nail hard on the head’), which appear throughout the novel.

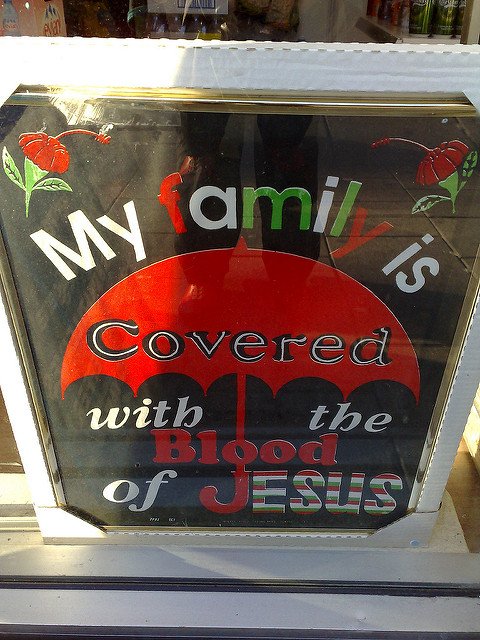

Religious hypocrisy is also portrayed when Giwa goes to visit someone who has a ‘THIS HOUSE IS COVERED BY THE BLOOD OF JESUS’ sticker on the door of his apartment. Once inside, Giwa notes that the house is not only well-decorated but has pictures of Jesus and biblical quotations on the walls. It turns out that the house belongs to a drug dealer and his live-in lover. The discussion that takes place between the visitor and the owner of the house definitely do not show the Christian nature of the man of the house. He tells Giwa later, ‘A good camouflage will drive suspicious eyes away from this room’ (p 109).

The biggest customers of the drug lords are the well-to-do politicians, including Chief Femi Otunba and General Hamza, whom the novel presents as one of the top government officials during the military regime. They promote crime and use youth as thugs. Furthermore, as seen in the novel, when these youth get into trouble, rather than save them, these men find a way to murder them.

Despite the beauty and breadth of thematic coverage, one must note, like Kolawole Ogungbesan in his essay ‘Simple Novels and Simplistic Criticism’, that a bad novel is not saved by a great theme. In many cases, there are tiny issues that can distort the works of even the best writers. For King of the Jungle, there are a number of things that together would form the novel’s albatross. The first is the slow-paced beginning of the novel, which might throw off impatient readers. The author struggles to pick up pace as we trudge through a genesis that might have been better off summarised. As the pages drag with nothing exciting happening, the narration becomes like the speech of the guest speaker whom we encounter on the first page, who prolongs his speech, ‘pausing at intervals to illustrate with anecdotes, and sometimes in Pidgin or Hausa [sic]’ (p 1).

Not surprisingly, character development is weak and takes time too. Also, there are editorial issues and tense inconsistencies. The linguistic flow of the narration at some points is somewhat odd, clumsy and cliché-ridden. A ready instance is found in the description of a lady whom Giwa comes across in the village:

Zainab was tremendously beautiful, but Giwa found her repulsive for two reasons: She had a rich Hausa accent which was superimposed on her English that irked him; secondly, she had a breath-killing odour that repelled Giwa. She, on the other hand, fell for Giwa, hook, line and sinker. She tried to engage Giwa in personal conversation but Giwa gave definite statements without a hint of emotion (pp 53–54).

Readers who are patient enough to read past the first part of the novel will be rewarded by the increased pace and range of the narrative. There are also splashes of humour, as illustrated above, and an increasingly action-packed narration that compensates for the defects that mar the first part of the novel.

Yadok’s novel can be said to be a younger sibling to Eghosa Imasuen’s Fine Boys. One notes that both novels look at family, cultism, friendship and loyalty, amongst other things. They are also set in the university system, and they both show how the lives of people are changed based on the decisions they take while in that ‘arena’.

In terms of geography, physical and human, King of the Jungle falls into the category of novels set in the Jos Plateau, as exemplified by writers such as Dul Johnson, Richard Ali and Edify Yakusak in the novels Deeper into the Night, City of Memories and After They Left, respectively. The theme of violence, particularly violence hinged on ethno-religious factors, is common to these novels. Yadok adds a large dose of criminal violence to his narrative. In all, Yadok’s book will do well with readers who enjoy realism and thematically engaging stories.

Photograph: ‘My Family Is Covered with the Blood of Jesus’ by Gilda

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.