By Ona Akinde

- Title: Diary of a Jewish Muslim

- Author: Kamal Ruhayyim

- Translator: Sarah Enany

- Publisher: The American University in Cairo Press

- Number of pages: 240

- Year of publication: 2014

- Category: Fiction

In the first half of the twentieth century, there were thousands of Jews living in Egypt. With the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, their lives in Egypt became increasingly difficult and many emigrated to Europe. Not only did the war have an effect on the status of things in reality, it led to a great absence of Arab Jews in African literature in Arabic. Kamal Ruhayyim, through his novels, tells stories that place Arab Jews not just at the centre of the novels, but as part of the fabric of Arab communities.

Exploring socio-political issues through fiction remains one of the most brilliant ways to shed light on these issues. While the reader enjoys a great story, their attention is also brought to these significant socio-political issues which the author addresses in the telling of the story. Kamal Ruhayyim does not fail to do this with his novels.

First in a trilogy, Diary of a Jewish Muslim explores the existence of Jewish Arabs as an integral part of the Arab community. Originally published in Arabic in 2004, it sets the direction for Days in the Diaspora (2012) and Menorahs and Minarets (2017), the second and third books in the trilogy. Diary of a Jewish Muslim is a riveting beginning to a trilogy that preserves the memories of Arab Jews.

Set in Cairo, Egypt, between the 1930s and 1960s, Diary of a Jewish Muslim accompanies Galal, a young boy with a Jewish mother and a Muslim father, through his childhood and adolescence in the vibrant neighbourhood of Daher. It reads like an extensive diary, with the reader seeing Galal’s life through his eyes, but right from when he is a baby.

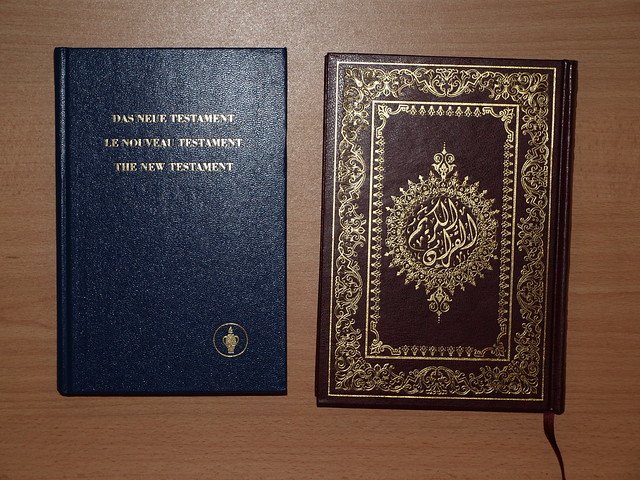

The title of the book gives away its core, with two key words: Jewish and Muslim. The entire book stages a conflict between these words and what they imply. How can these two coexist? It is a question Galal spends most of the book trying to answer. It is the bane of his existence. The reader follows Galal on this journey to discover himself and his identity.

Galal is raised by his mother and his maternal grandparents. His father dies in the Suez War of 1956, when he is only a baby, leaving Galal with no memories of him, an absence Galal tries futilely to fill. He grows up in a largely Muslim community, all his neighbours and childhood friends being Muslim. Ordinarily, he should blend in like every other child, but he sticks out like a sore thumb. The fact that his mother and her family are Jewish is something that simply cannot be overlooked, and it is a label he will constantly struggle with.

Galal is constantly torn between two extremes. He grows up on one hand, experiencing his grandmother’s hate for Muslims, with his mother making little or no effort to reassure him that there is nothing wrong with who he is. On the other hand, he is faced with forces outside the home that further fuel his conflict. Early in his childhood, his friend says to him:

You idiot; don’t you know you’re Muslim? You’re every inch a Muslim. Your mother and her family, Heaven protect us, they’re the ones who are Jews…. Yes, Jews. And Lord, what’ll happen to them on Judgement Day! Straight to Hell (p 34)!

It is one of the instances in the book that throw Galal deep into his identity crisis. His grandfather is his middle ground, telling him on multiple occasions that Jews and Muslims can coexist, that they are contained in each other’s books. Jews are ‘People of the Book’ and Muslim prophets are found in the Jews’ Torah.

Galal’s family spends most of their lives around Muslims, and so do the Muslims in their lives but the lack of tolerance both parties have towards each other is evident throughout the book and takes many forms. We see it in how unwelcoming Galal’s father’s family is towards him and his mother, in how Galal’s mother views Muslims, including his father’s family, and in the sentiments their Muslim neighbours have towards them. With the way Galal’s mother views his father’s family, it is hard to believe that his parents were ever in love, so when she tells Galal how they met, it is definitely a shock to the reader. If there is one thing the reader realises, it is that, sometimes, love is not enough and will not conquer all.

This religious intolerance is a thread that runs through the entire book. Its effect is so strong that it forces Galal’s grandparents, and eventually him and his mother, to emigrate to Paris. It is a decision that many Arab Jews had to take, even in reality.

Throughout Galal’s journey, the stigma that comes with being born of a Jewish woman is strong and evident; it never stays hidden for long. Galal faces discrimination in various forms and is bulled in school but where the stigma hurts the most is when he, as a teenager, falls in love with a childhood neighbour, Nadia. Galal initially struggles to win her over, but when he finally does, his joy is so contagious that it has the reader rooting for their relationship, hoping that for once, nothing stands in the way of Galal getting what he wants. Their relationship changes him for good: he is more driven, more ambitious and determined to be the best man he can be for Nadia. Just when it seems like things are going as planned, the stigma takes this away from him. When news gets out that Nadia and Galal are in love, Galal never sees her again. Her family does not want anything to do with him and they move out of the apartment building, just to get away from any stigma that may stick to them from being associated with him and his family.

Most importantly, Ruhayyim explores the ways in which Galal’s identity and his life in general are affected by being a Jewish Muslim. For most of the book, Galal does not fully embrace his identity as a Muslim. It is merely a label for him, just the way being Jewish is. As the book progresses, he tilts towards embracing his identity as a Muslim and has defining moments that seal things for him. Prior to these experiences, he could not recite verses of the Koran, he did not fast, pray or go to the mosque often, but at the burial of one of the communities’ significant sheikhs, Galal is overcome by a sense of conviction:

It was as though my feet were weightless, and I was soaring through the air. All at once, I was overcome by a paroxysm of weeping and sobbing as I called out, “There is no god but God, and Mohammed is the Prophet of God” (p 177)!

It is a moment that defines the course of his life going forward.

His being Muslim, however, does not change the fact that he has a Jewish family and this constantly puts him in the middle of tension with his mother and his grandmother. He gets into fights with his mother over religion and goes as far as getting a sheikh to convert her, causing his mother to stop speaking to him for two weeks, and when he moves to Paris, he gets into fights with his grandmother over his choice to be Muslim. The only person who is accepting of him as he is, is his grandfather. Galal spends most of his childhood and youth trying to resolve a conflict that he did not even create.

While telling Galal’s story, Ruhayyim does not fail to capture the sights, sounds and tastes of Cairo. The descriptions in the book are vivid and explicit. Buildings are described down to the last window, streets are described down to every element that makes them up. It is a wholesome reading experience that allows to reader to live Galal’s life with him, as the words paint clear pictures of his experiences.

Towards the end of the book, the reader begins to feel some hope for Galal on his journey. It appears that finally, Galal will find the respite that he deserves, that the identity crisis is over and he will walk on a path that he has carved for himself but when the book ends, this hope is snatched from the reader. What is left is a feeling that surely, this cannot be Galal’s end. The Galal we meet at the beginning of the book is not the Galal we see at the end and it is evident how much all his experiences have now shaped the man that he is. The beauty of the ending lies in the fact that it brilliantly creates in the reader, a desire to know what lies ahead for Galal, thereby giving room for the rest of the books in the trilogy.

Diary of a Jewish Muslim is a significant addition to African literature centred on Arab Jews. It does exactly what Ruhayyim seeks to do with his books: it documents the lives of Egyptian Jews in ways that keep their memories alive.

Photograph: ‘Holy Books’ by Tarek

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.