- Title: The Road to Jamaica: Poems, 1968–1970, and New Poems, 2012–2013

- Author: Syl Cheney-Coker

- Publisher: Karantha Publishing House and Sierra Leonean Writers Series

- Number of pages: 67

- Year of publication: 2015

- Category: Poetry

In 2014, Richard Oduor Oduku wrote an essay that was essentially a lamentation. He was worried about his old, unpublished poems, about the fact that those poems might not be a good representation of his evolution and current thinking, about the fact that his old voice, which bore witness to a part of history, could be lost to time. At the end of ‘Where Do Old Unpublished Poems (and Stories) Go?’ he asks these questions:

Still, in your own life as a creator, where do your old unpublished poems (and stories) go? Do they acquire a life of their own and live undeterred in the darkness inside box locks or digital backups? Are they historied or they die off and reincarnate as new poems and stories?

It is safe to assume that some of those old, unpublished poems will never get a chance at publication. In the aforementioned essay, Oduku gives a voice to a communal struggle. This struggle is particularly prevalent among creators whose art is transmitted through the page. But the truth is, any creative work from whatever stage of the creator’s life, irrespective of the medium of transmission, can be lost. It can be lost to the audience. It can be lost when it goes out of print. It can be lost after the performance artist dies, stops producing or ceases to be relevant to her time. Therefore, the most appropriate question to ask remains where do lost works go? Like love, are we supposed to find them, lose them and work towards finding them again?

Syl Cheney-Coker’s find came through the letter box. A girlfriend from his university days thought he might want to read his old poems again, so she posted them to him. Over forty years after these poems were originally written, they have now been published. In a note prefacing The Road to Jamaica: Poems, 1968–1970, and New Poems, 2012–2013, he writes:

Now, four years after they resurfaced, I have finally decided to publish the volume. With the benefit of wisdom and the eyes of a much more mature poet, I have completely revised nearly all of the poems (p vi).

So, are these poems necessarily old? Is this volume the same as what he originally wrote, or do these new poems just borrow themes from the old ones? These questions lead us back to what we might as well call Oduku’s lamentations for the loss of artistic innocence, an elegy for the coming of age of the poet. This is in contrast to Cheney-Coker who celebrates maturity.

The Road to Jamaica is a volume in two parts. The first part is titled ‘The Road to Jamaica’, and is made up mainly of the remnants of the old collection. The central themes of this first part are African history and expression in the context of the colonial establishment. This section begins with the poem that gives the collection its title.

‘The Road to Jamaica’ chronicles the journey of Africans to the New World. Jamaica symbolises the Caribbean, where many of the slaves ended up, in plantations. The title poem is a tribute to those slaves and their diverse origins.

‘The Prince of Wales School’ talks about a school founded in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The founders wanted to make Englishmen out of the African pupils. It tells the story of the poet who, as a boy, enjoyed the ritual of being a student until he grew wary of an education that sought to make him English. We learn of his tendency to question the system. He is moved to define himself as an African.

The other poems in this section are written for prominent figures in the African struggle and to show the good side of indigenous African culture. These poems are littered with allusions to history, places and people. The last two poems in the section are, however, autobiographical.

In ‘Ode to my Pipe’, the poet writes about his love for the pipe. He eulogises the pipe because it is the only thing that has been faithful to him. In the last poem in this section, the poet reveals that he does not want to write plays but enjoys the theatre. These last two poems launch the next section of the volume, ‘Elegy for the Afro-Saxon’. Here, the poet departs from the themes that he traditionally writes on.

His three collections of poetry, Concerto for an Exile: Poems (1973), The Graveyard Also Has Teeth (1980) and The Blood in the Desert’s Eyes: Poems (1990), largely engage his interrogation of his identity and place in the poetic world, both as a nationalist (in the second volume) and as prophet (in the third volume). With the benefit of hindsight and age, Cheney-Coker reflects, in the poems in ‘Elegy for the Afro-Saxon’, on the life that he has led. Even in these poems, which are deeply autobiographical, the poet takes swipes at colonialism.

‘Not Love at First Sight’ is about his first visit to London, a city he came to love. It is difficult to miss the poet’s love for music in his poems. Even in his references to poets, both Africans and non-Africans, he chooses those who are notable for the musicality of their poetry. In ‘Unfinished Musical Matter’, he talks about his practice as a musician and how that connects him to his father. Like in other poems, he hints at the stereotypes and misperceptions that came to define his career path.

The poet’s allusion to songs and musical instruments takes on different meanings in different contexts. ‘New Songs’ is a carrier of memory and a bridge between two different worlds. Buried in the songs are history and keys to the discovery of the self. Even though they are new songs, they are just a piece of the cloth that history is. In the poem, the poet imagines history as a continuous variable.

‘The Tom Tom’ is a drum used not only for calls to celebration but also for calls to conversation. It heralds a festive mood, that period when differences are buried and all attention is focused on only one thing – the music.

The secret of musicality lies in the ability to maintain balance. It is easy to tip over into a flat prose masquerading in verses as poetry. There are many poems in this collection that are prosaic. Some of stories in the collection could serve better in the poet’s memoirs or in an autobiography.

Where then do we place lost-and-found, unpublished poems? The publication of The Road to Jamaica in 2015 seems to beg the question of relevance. Although these poems might seem lost to contemporary conversations and concerns, we have to bear in mind their history. In 1973, when the poet first announced the existence of the old poems published in this volume, their themes were relevant to the conversations current at that time. Make no mistake, Cheney-Coker is the finest modern poet that Sierra Leone has produced till date, but that judgment cannot rest solely on this volume of his work.

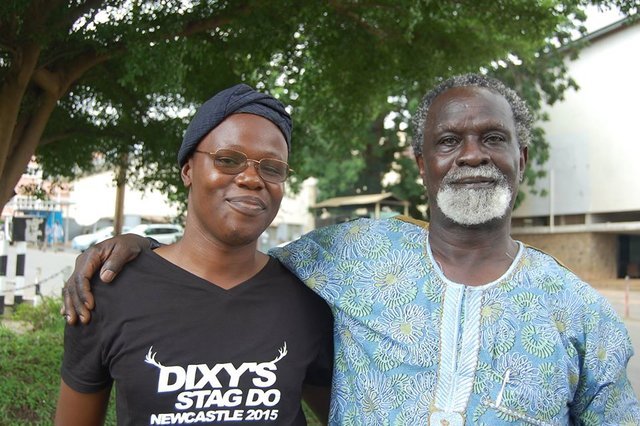

Photograph: ‘Syl Cheney-Coker and a Younger Poet’ by Servio Gbadamosi

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.