- Title: Anubis

- Author: Ibrahim al-Koni

- Translator: William M Hutchins

- Publisher: The American University in Cairo Press

- Number of pages: 184

- Year of publication: 2014

- Category: Fiction

Anubis is a novel that needs to be read like a sacred text, which implies reading it more than once. First, for its density and layers of meaning – the book is like a rich archaeological site that must be revisited, again and again. Second, the reader will derive great pleasure from the beauty of the book’s language.

In the ‘Author’s Note’, al-Koni explains that he first wrote the novel in his mother tongue, the language of the Tuaregs, before translating it into Arabic, which he learnt at the age of twelve. Perhaps the fabric of meaning may get torn in translation, but the intricate weaving of words in the novel compels the reader to appreciate William M Hutchins’ effort in bringing into English what must be the capacity of the original to regale the reader as well as its linguistic intensity.

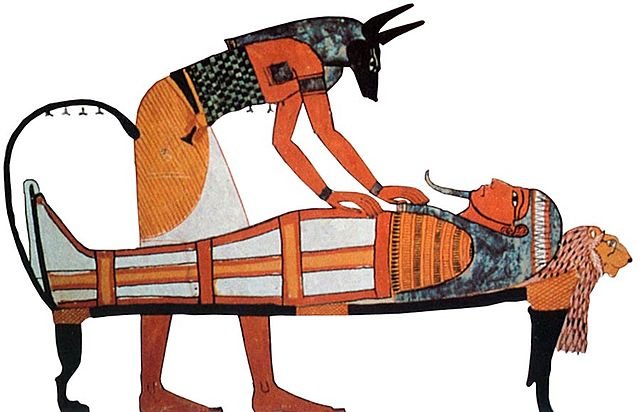

Anubis is a novel full of beautiful passages of sheer lyricism, and al-Koni’s use of the legend of Anubi to tell the story of humankind is best seen as a meditation on the quest for identity. Al-Koni explores the tribulations of Anubi, the Egyptian legend also known among the Tuaregs as the keeper of tombs, and he uses these explorations to capture the continued search of humans for identity, knowledge and truth. In the novel, the author’s thesis is that we are all in this search for identity together. We are all Anubis.

In an interview with the Louisiana Channel, al-Koni first seeks to establish the ‘existential metaphysical dimension of the desert’ then he asks, ‘How does a writer write about a metaphysical place?’ It seems that the novel, Anubis, is his answer to that question.

It may be said that Anubis presents the make-up of the human being, the layers of emotion that give rise to acts of compassion, greed and lust. The novel is a presentation that draws on experiences of the desert and the difficulties of that terrain. In the process, the book also provides insights into the nature of wanderlust among the Tuareg.

Anubis is about a Tuareg youth who ventures into the desert in search of his father, in a society where a search for one’s father is seen as an anomaly, the mother being the centre around which the child’s life is expected to exclusively revolve. This venture to find the father is foiled by spectres, spirits and by the protagonist’s sister, who eventually becomes his lover and then transforms into the sibylline priestess who bears him a son. The search for knowledge, symbolically represented as the search for a father, may best be seen as the search for a truth that in essence must be worshipped.

Anubis is a windy story in which the author tries to fit the many attributes of the eponymous legend into the main character, from morphing into half-animal, half-man to living in a tomb, all of this can be interpreted as part of the protagonist’s quest for truth and for self.

The novel is divided into three parts, ‘Cradle Talk’, ‘Passionate Talk’, ‘Grave Talk’, and it ends with a collection of Tuareg sayings, which is titled, ‘Aphorisms of Anubis’. Each of the three parts of the book opens with quotations from the Bible and unveils the development of the main character. In addition, each part is further broken into eight sections, each named according to a period of the day, as if the narrative itself is built around the concept of time, which then graduates into an exploration of man’s continual search for purpose, for meaning.

The metamorphosis of the characters in the book offers us a journey into a complex of events, not just for the sake of enjoying the novel but also to deepen our understanding of existence as a whole. Right before our eyes, we witness the making of civilisation and the emergence of a ‘unique identity’. The way al-Koni interrogates identity in Anubis is best described in an Alaa Khaled essay, ‘Unique Identities’, from the Identities in Motion project, where Khaled discusses the main character in another novel, Hay bin Yakzan, written by the Andalusian, Muslim polymath, Ibn Tofayel. Khaled explains that the owners of unique identities:

[H]ave acquired the unique ability to meditate and draw conclusions at an earlier stage. They were born old and mature, as Christ was born, who defended his mother as a newborn.

Khaled goes further to say:

[Owners of unique identities] have all lived in the lap of a miracle, and serendipity played a key role in their lives and reinvented a once forgotten path as their relationship with the animals. They exist to prove or add a new way of life or the revival of an ancient one. They are closer to the prophets, but without followers or a community. They also live their important journey in a secluded place, in a laboratory, an empty island a place where they can discover their identity from within, and not as a reflection of an eye that looks from the outside.

Wa, the main character in Anubis, who in a different manifestation is Anubi, asks his mother, ‘Where did I come from?’ And though she answers him with ‘Same as everyone’ (p 13), his quest to discover himself continues. When this same question comes up again at another point in the novel, it becomes evident that the author is seeking to advance his exploration of identity as the carrier of ‘disruptions, restlessness, longings and hunger’ (p 95), which is why the main character creates a statue to be worshiped and a religion that would create order in the midst of chaos – creating history.

In The Art of Loving, Erich Fromm claims that every human is in a continued search to answer the question of ‘separation, to achieve union, to transcend one’s own individual life and find atonement’, and that the religions and philosophies of different cultures, by their sheer number, only highlight the limitations of the available answers. The solution remains something that every generation attempts afresh.

This is noted in the last paragraph of the novel, where al-Koni writes:

My insane desire to transform dream into reality endowed me with sufficient strength until I was able to light a fire and then trace on a square of leather a final symbol that would provide evidence for future generations of the reality of Anubi, who was neither a shade nor a figment of the imagination but a man, who once crisscrossed the desert (p 168).

By emphasising the reality of Anubi as a man who once crisscrossed the desert, al-Koni treats the received narratives of Anubi as legend, not myth. The reader could interpret this to mean that humans created religion to elevate their search for self. But it is important to note that the statue is first a work of art – aesthetically adored – before it grows into an object of worship. In essence, a subtle interjection in the whole narrative of existence is that art comes before religion.

Now, returning to al-Koni’s Louisiana Channel interview, where he says ‘the home of the novel is man, not the place’, we realise that even before Wa begins his physical journey, his mind is already in turmoil, ready to move. In the novel we read:

The sword that smote the darkness of falsehood and limited the intimate congruence between desert sky and desert land did not burst forth from some spot in the eternal unknown but from inside me (p 5).

It is equally important to mention that the Tuareg spirit of freedom is that which propels the main character into the unknown. In the conversation Wa has with a priest, who would later morph into his father, the former asks, ‘Does freedom cause us to lose ourselves, master?’ The priest responds, ‘Freedom, my son, is about living, not about dying’ (p 25).

The reader will discover the soul of the book in Part Two, ‘Passionate Talk’ especially, the chapter ‘Dusk’, where the main character is faced with the highest degree of trial, separation from ‘the herd’, separation from community, which is actually a hunger, a thirst. Wa finds himself conversing with a spectre, who tells him that, ‘It is not wise to neglect what we have in order to search for what we lack’ (p 78). The dialogue here explores the core issue of self, of knowledge, of identity, and brings meaning to the symbolic presentation of Anubi as a race – our humanity, or al-Koni’s historical fictionalisation of the Tuaregs. And this is exemplified in these lines:

Each one of us is Anubi; each a fleeting shadow.

But [who] are you?

I am a fleeting shadow (p 80).

Anubis is a poetic treatise on the spirit of the desert. However, even though the desert inspires this narrative, the Bible appears to have a strong influence on its structure. The birth of Wa is Genesis, and when Wa creates a settlement, just as after God created earth, he rests:

I entered it on the seventh day to rest and stretched out in its cavity, which embraced me as a nest embraces fledglings. It swallowed me the way a tomb swallows the corpse. I liked this image so much that I named my cosy nest azkka (p 94).

Anubis reminds us of how some people spend most of their lives reading the Bible to derive new meanings. Anubis is not an easy read. It requires patience and diligence, and in return the reader is assured of exquisite satisfaction – perhaps something close to a spiritual uplift.

Photograph: ‘Egypt Balsameringsguden Anu’ by FinnBjo~commonswiki

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.