- Title: Son of Man

- Author: Amara Nicole Okolo

- Publisher: Parrésia Publishers Ltd

- Number of pages: 118

- Year of publication: 2016

- Category: Fiction

I am the story he wanted to publish. Each sentence simmered in bowls of wrath. The letters were fiery, their message scalding. I was eager to read, thirsty for attention. But as with every fateful story, I was rejected and put away because of my honesty, because I spoke the truth. And in 1996, nobody could handle my truth.

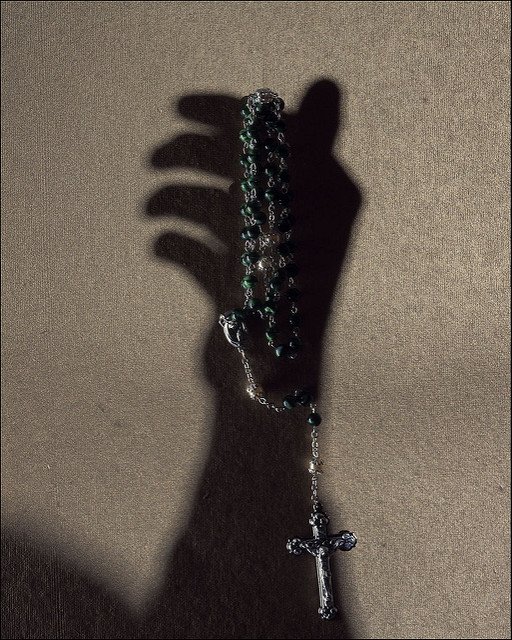

In this collection of six short stories, the author employs inanimate objects – a pair of worn shoes, a machete, a rosary, amongst others – to tell stories about human beings, the not-so-perfect world they live in and how it has affected them adversely. The stories have a common thread running through them: how the system has failed the citizens.

The stories deal with multiple themes: hatred, love, police and military brutality, and the consequences of a failed system. The author writes in a simple, flowing style which nevertheless strikes at the core of what is wrong with the society.

In ‘Talking Shoes’, the narrator is a pair of tattered shoes worn by a desperate man, Andrew, who searches unsuccessfully for a job. He is described by the shoes as a failure:

Our owner Andrew resembled our wear and tear: matted uncombed hair, chin shadowed with stubble, eyes red rimmed from sleepless nights. His borrowed suit was a size too big for him and drowned his gaunt figure.

His wife concurs:

A useless miser…. A lazy old swine with nothing but forged certificates! Six months gone and all you do is wear these tattered shoes and yeye suit’.

After yet another unsuccessful interview, and down to his last five hundred naira, he decides to commit suicide but changes his mind just in time through the redemptive love of his two young daughters.

‘The Machete of Retribution’ is told by the machete that Ejiofor, a farmer, uses to cut palm bunches, grass and firewood. Ejiofor’s son falls gravely ill but the nurses at the health centre are unable to attend to him because the system has not trained them properly, resulting in his death.

‘The Lost Ones’ deals with police brutality. Gabriel, the protagonist, plans to find a decent house for his parents and siblings but due to a mistake, he finds himself illegally detained by the police. While in custody, he discovers he is not alone. Worse, some of the other young men are taken away in the middle of the night, never to be seen again. While in the cell, he overhears the most chilling conversation between two policemen concerning two young brothers. One policeman tells the other to ‘Go Counter, tell Mabel make she tear out that sheet with these boys them name. Tell her to rewrite a new list’. All Gabriel can think of is that the brothers will never see their families again.

‘Speak, We Are Listening’ is narrated by an unpublished story. It centres on a young journalist, Kola, who writes a story critical of the then military government. The story, a ‘fiery’ one with a ‘scalding’ message about abduction and missing persons, is dismissed as frivolous by his editor. He subsequently joins a group of activists, Revolution against Assault, Guns and Enemies of Democracy, who declare, ‘We intend to use our creativity for a peaceful revolution against government’. This is a recipe for death in a society where military tribunals have usurped civilian courts and there is no more freedom of speech or hope for justice.

‘500 Dreams and a Letter’ is related by a rich but embittered, cancer-ridden, old man on his deathbed. He once tried to commit suicide but is now determined to inflict psychological pain on seven of his eight children whom he believes are simply waiting to inherit his estate when he dies. He refers to his children, whom he hates, as biological garbage.

‘That Fine Madness’, tells of the ill-fated love between Achike, who is bipolar, and Rahila, who is married to an old man she detests. The story is related by a rosary given to Achike by his mother. Rahila’s love calms Achike down but when she inexplicably disappears, he descends into madness.

As in some of the other stories, the author occasionally presents confusing perspectives. When, at the beginning, the rosary describes Achike as ‘an unbelieving piece of walking filth’, this reader is confused because at no point does Achike demonstrate any sort of aberrant behaviour; rather, he defends Rahila when her husband beats her and prays to God when she disappears. Moreover, the rosary is an aid to Catholics in saying their prayers. How can something so sacred describe a mentally ill man in this manner?

Overall, the author employs an objective narrative style in all but one of the stories. She also utilises a powerful descriptive style, as in the following:

Home was Oshodi, its mangled buildings like hunchback trolls. The refuse dumps filled with colourful remains of household waste dotted the roadside like decorations. The gutters were clogged with mucky smelly waters…. Ghetto they called it, but we called it home.

Son of Man is a pleasant read, despite the many typographical errors. Some of the stories certainly compare favourably with the author’s newer work, such as ‘The Things We Never Say: A Family History’, published after the collection under review, which explores the themes of love and hate, and which has enjoyed a warm reception.

Photograph: ‘rosary’ by Linda Flores

Comments should be sent to comments@wawabookreview.com. Please use the appropriate review title in the email subject line.